The Reds are conducting an experiment that may change the game defensively

Cincinnati Reds ace Luis Castillo was under duress in the opening inning of the season last week. The St. Louis Cardinals had already scored and the bases were loaded with one out. Yadier Molina entered the batter's box.

Hoping to induce the slow-footed catcher to hit into a double play, Castillo executed his next pitch as intended: a breaking ball tracking for the outside corner. Molina pounded the pitch into the turf, bounding toward the left side of the infield. Reds shortstop Eugenio Suarez ranged to his right, briefly collecting the ball before bobbling the transfer to his throwing hand. The ball trickled into shallow left field and two Cardinals scampered home. By the end of the inning, St. Louis had scored six runs.

The most remarkable thing about that play? The Reds chose to place Suarez there. He hadn't played an inning at the position since 2018; he hadn't played more than 11 innings there since 2015 before his move to third base. We think of players sliding down to less demanding positions as they age. We don't often see players at 29 years old move up the defensive ladder.

"We wouldn't be doing this if we weren't confident that he could do it," Reds manager David Bell told reporters this spring.

The Reds likely would not be conducting this experiment if shortstops were seeing opportunities like they were in, say, the 1980s. Playing Suarez at a premium position is not as wild as it seems. With fewer balls being put in play in the majors, defensive opportunities have been reduced. Some positions are losing more defensive work than others, including some of the most important positions on the field.

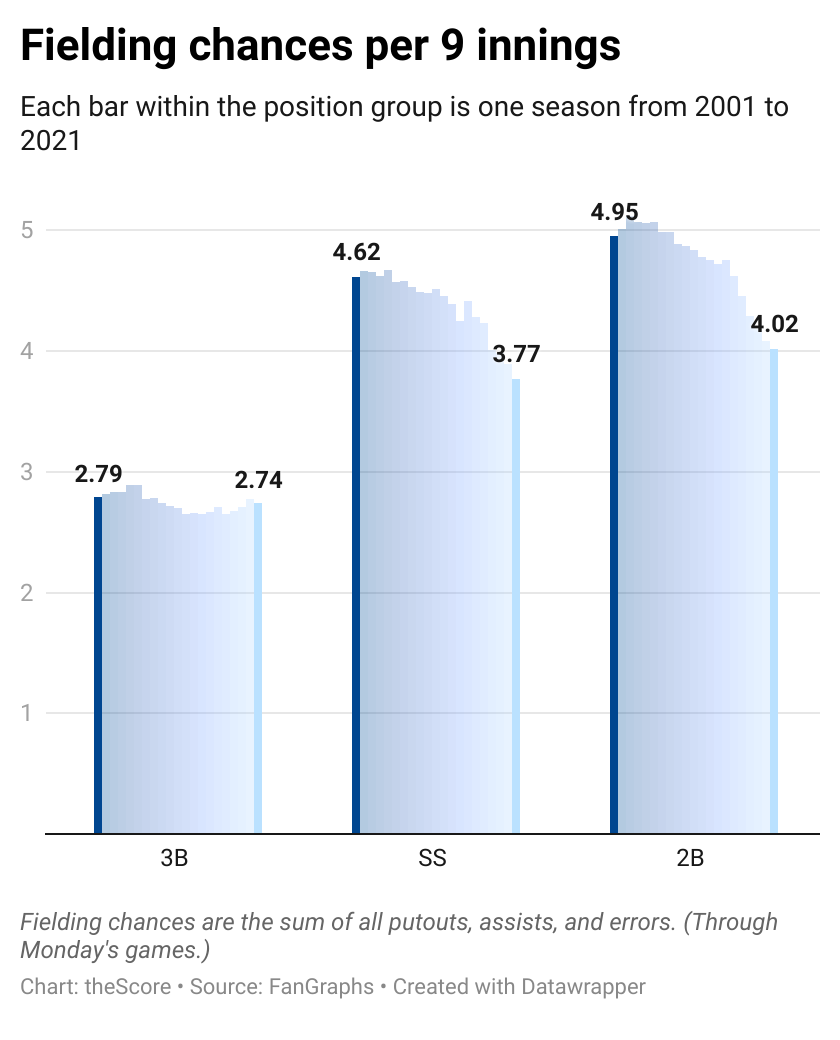

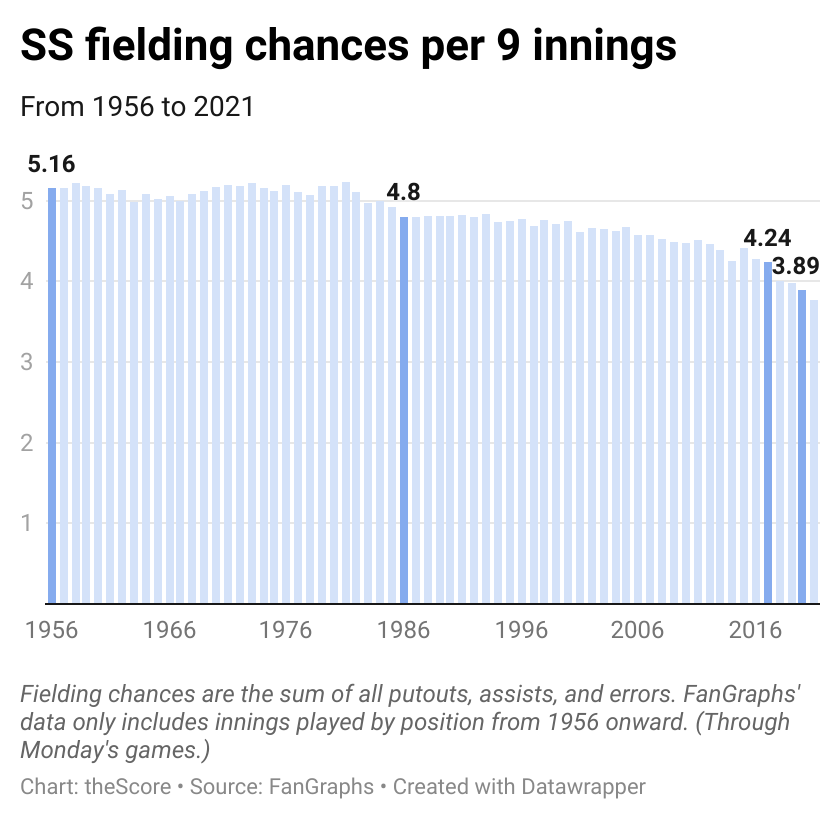

The number of fielding chances per nine innings for shortstops decreased 16.7% from 2005 to last season, from 4.67 chances per game to 3.89. Entering Tuesday, chances were down again, to 3.77 per game, or 19.3% off the 2005 mark.

The sum of putouts, assists, and errors at the position are down 28% compared to levels 40 years earlier.

The change is accelerating. The opportunities for shortstops only slightly declined from 1956 (5.16) - the first year such data is available for all positions at FanGraphs.com - to 1986 (4.8), a 7% decline. There was an 8% decline between 2017 and 2020.

And it's not that fielders are less able to get to balls, batted balls in shortstop zones are declining even more: early season levels are down 32% from 2005.

Hitters have focused more on trying to beat infield shifts by going over them, and strikeouts - the chief culprit behind fewer balls in play - continue to rise. This season, the strikeout rate sits at 25% - an all-time high.

"Defense is less important than in the past with all the strikeouts," one American League executive said. "Yes, we should be able to put traditionally worse defenders in the infield. How much worse? I don't know."

That is the question. How much can teams get away with? Suarez made his fourth error of the season Monday at Arizona. He owns a .892 fielding percentage. That's a great conversion percentage for a shooter at the free-throw line, but not for a shortstop. Excluding last year's shortened season, there hasn't been a qualified shortstop to post a sub-.900 fielding percentage in more than a century.

While shortstops have lost significant chances, second basemen have lost the most work. Second base is where the Reds had been playing Mike Moustakas before the Suarez move allowed him to shift back to his natural spot at third base.

"None of these decisions are made in a vacuum," said an NL scout. "If you have strength in other areas, I think it's probably easier to make a risky defensive-positioning choice."

Last year, second basemen had 20.3% fewer fielding chances compared to 2003. There were 5.12 chances per game in 2003 compared to 4.08 last year. They're down again this season to 4.02.

Since 1981, second base chances are down 28.6%. That decline, and defensive shifts, are changing the athletic requirements of the position.

"A second baseman now can be a bit less agile as he is already at the bag, or nowhere near the bag, (compared) to past … he might need a stronger arm," the AL executive noted. "Third base experiences more range plays than in the past."

Unlike shortstop, second base, and first base, third base opportunities have held up remarkably well.

Early this season, third basemen are active on 2.71 chances per game, which is in line with the last few seasons and similar to 1990s levels. The third baseman is often the lone defender on the left side of the infield in many shift alignments. Some teams will also swing their third baseman around to be the third defender on the right side of the infield during a defensive shift against a left-handed batter.

The Reds aren't exactly going full Satchel Paige and waving their outfielders in before striking out the side - but they are as well-positioned as any team to continue making bat-for-glove trade-offs.

Entering play Tuesday, Reds pitchers were tied with the Brewers for the major-league lead in strikeouts (712) since the start of the 2020 season. Perhaps that's why Reds GM Nick Krall told reporters the club began kicking around the idea of playing Suarez at shortstop last season. Krall said he was convinced Suarez could get the job done this January after seeing him in better shape.

The Indians are the AL leader in strikeouts since 2020. And like the Reds, who entered the season without a true shortstop, Cleveland departed spring training without a true center fielder. The club experimented with shortstop Amed Rosario there - he made three errors in his first spring game. In recent years, the Indians have also tried Lonnie Chisenhall and Jason Kipnis in center field, awkward fits at the position.

But compared to infield opportunities, the outfield hasn't seen much decline as batters swap grounders for liners and fly balls.

Chances in center field are within the modern era range, which is between 2.9 and 2.4 chances per nine innings. Last year, CFs had 2.46 chances per game. This season it stands at 2.55.

Opportunities in the outfield corners are down early this season at historic lows, less than two per game at each spot. But in 2020 (1.85 left field, 2.06 right field) and 2019 (1.85 left field, 2.06 right field) the opportunities in the corner were near the middle of the pack since 1956.

When it comes to the infield, perhaps we'll see more experiments from more clubs.

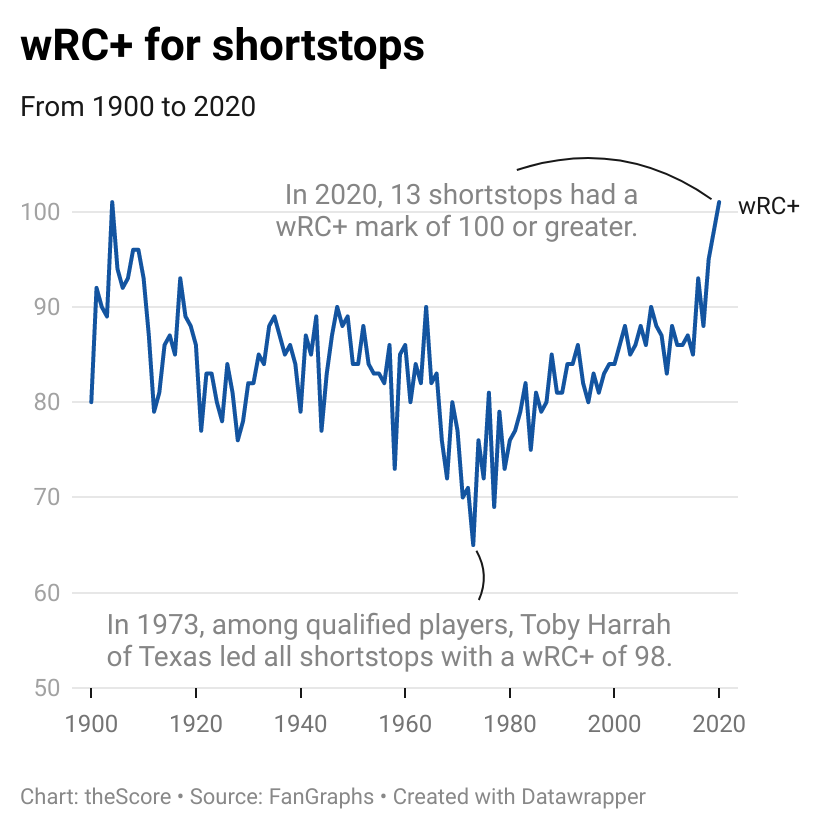

Outside of catcher, most positions have become more offense-oriented. For example, two of the top three offensive seasons all time for the shortstop position occurred in 2019 and 2020. Last year's 101 weighted runs created plus mark (wRC+) - a measure that adjusts for ballpark and run environments where 100 represents league-average production - tied the top mark set in 1904. It was just the second time the position has met or exceeded league-average offensive production.

This is part of a larger story about the game's march toward three true outcomes and fewer balls in play, and whether or not that needs to be remedied. The commissioner's office is concerned about how warped the game has become. Even as MLB said it's using a less lively ball this year, home runs continue to fly out of parks. Strikeouts continue to rise. And with fewer balls in play, some teams are trying to jam more offense into traditionally glove-first positions.

MLB has even floated the idea of eliminating defensive shifts, which may in part have an eye on increasing defensive demands on positions. But until MLB intervenes, it seems the glove-first player is becoming endangered.

Travis Sawchik is theScore's senior baseball writer. Follow him on Twitter at @Travis_Sawchik.