What happened with Rich Peverley’s heart, and how it affects his future

Sudden cardiac arrest. The absolute last thing you want to hear as a player is hustled off the bench after a collapse. It rarely has a good outcome, but Rich Peverley and the medical staff of the Stars and Blue Jackets have beat the odds.

As part of preseason physical testing, Rich Peverley had an EKG that showed a “blip” (a term I apparently wasn’t fond of).

EKGs can have rhythm changes or findings suggesting anatomic changes, but not blips. Quit dumbing it down.

— Jo Innes (@JoNana) September 12, 2013

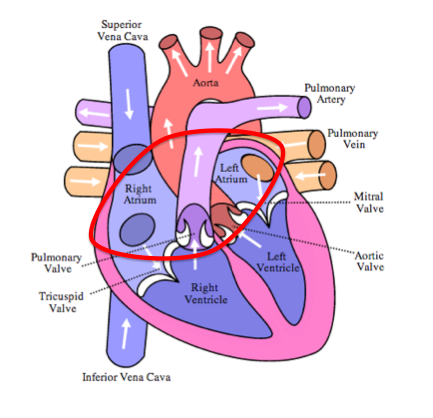

It turns out the blip was atrial fibrillation (afib) – the most common arrhythmia, present in about 5 million Americans. It happens when the part of the heart responsible for setting the pace doesn’t do its job properly, explained quite eloquently here (Pevs forgive me for the heinous misspelling):

So about Rich Peverly - atrial fibrillation (afib) is when you have a pissy little spot in the heart that gets the rhythm out of whack.

— Jo Innes (@JoNana) September 13, 2013

Afib is exactly what it sounds like – the atria (upper chambers of the heart) don’t squeeze in a nice organized regular manner – they fibrillate (quiver). That increases the likelihood of stroke because blood doesn’t zoom through, it swirls around in the atria. Blood standing still is blood that likes to clot, and clots are things you don’t want in your body. The ventricles are responsible for pumping blood out of the heart to the lungs and the body, and they’ll keep doing their job, just irregularly as they follow the irregular impulses sent down from above by the pissy atria. Afib is something a lot of people live with (on anticoagulation), but in someone like Peverley, it had to be fixed. The odds of sudden cardiac death are already doubled during physical activity, and hockey is a sport with a lot of very intense activity in short bursts, which also increases cardiovascular risk.

Peverley had an ablation, a procedure where a catheter is threaded up into the heart through vessels in the leg in order to ablate (destroy) the source of the arrhythmia. Once the catheter is in place, an electrophysiology study is done, where electrodes on the end of the catheter measure the electrical activity in the heart during the arrhythmia. The problem areas are then ablated using radiofrequency pulses (essentially burning the spots) or cryoablation (freezing them). After an ablation there’s nothing to keep an athlete from returning to their sport assuming they’ve gone four to six weeks without recurrence of their arrhythmia. The success rate of ablation varies depending on what study you look at, but the consensus is that at around two years 60-80% of people are still symptom-free. While afib can be treated with drugs, they’re not perfect either, and they can have side effects. Drugs that don’t allow you to increase your heart rate aren’t going to work for an athlete, hence the decision to ablate.

What the hell happened on the Stars’ bench?

Rich Peverley finished a shift not even halfway through the first period and skated back to the bench. While seated, he collapsed suddenly. Teammates yelled and banged their sticks to get the attention of refs, trainers, doctors, and anyone who would listen. Within seconds of the collapse, medical staff picked Peverley up and hustled him down the tunnel. Dr. Gil Salazar, an emergency physician from UT Southwestern explained what happened next:

“We provided oxygen for him. We started an IV. We did chest compressions on him and defibrillated him, provided some electricity to bring a rhythm back to his heart, and that was successful with one attempt, which is very reassuring.”

Translation: Peverley’s heart stopped suddenly. He got almost instantaneous CPR, he got shocked, and he survived. After a single shock he regained consciousness, and wanted to know if he could get back in the game. Peverley beat the odds in a huge way. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest isn’t something people generally survive. Again, studies vary, but a survival rate of two to ten percent is what’s generally seen. With the addition of an automated external defibrillator (AED), survival increases significantly – as high as thirty percent (read about ithere). Early CPR, early defibrillation, medical staff who know their shit, and a young healthy guy with a heart arrhythmia all came together in exactly the right way. Afib increases your chance for sudden cardiac arrest, because it can degenerate into fatal rhythms (the kind that respond to defibrillation). Notably, Peverley was out for a game last week after he “felt strange” – possibly a recurrence of his afib.

What now?

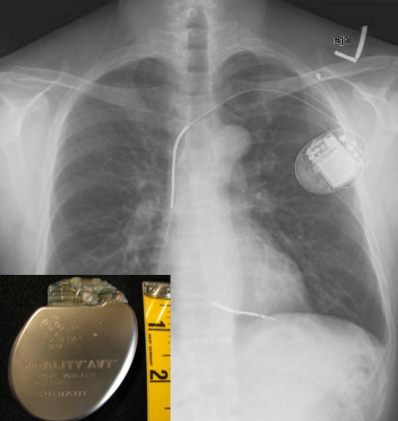

Peverley is in the midst of a battery of testing to determine what happened, and if there’s any damage from his collapse and resuscitation. An EKG to determine what heart rhythm he’s in, an echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart), possibly another catheterization and electrophysiology study, and continuous monitoring in case he develops another arrhythmia while he’s admitted to the hospital. Plus of course a chest x-ray to make sure he doesn’t have any broken ribs from the CPR (which is notoriously brutal). The problem with sudden cardiac arrest is that it can happen again. If whatever caused it can be identified and corrected, great. Having said that, most people who go into the hospital with sudden cardiac arrest come out with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). Even if testing can identify a reversible cause (like something that can be ablated), it could happen again. The only way to ensure you get prompt defibrillation no matter where you are is to carry your defibrillator inside your chest. Having an ICD makes a hockey career difficult – you have to worry about dislodging the leads every time you get plastered into the boards (or plaster someone else into the boards).

Chris Pronger and Jiri Fischer – Similar but different.

In 2005 Detroit’s Jiri Fischer collapsed on the bench in what initially looked like seizures. Medical staff attended to him, started CPR, and cameras cut away as the announcers realized what was happening. Fischer was also defibrillated, and was also successfully resuscitated. The difference is that Fischer had a genetic structural cardiac condition – hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). The heart muscle is thickened, muscle fibers aren’t arranged in the usual way, and there’s a predisposition to arrhythmias. The American Heart Association recommends that people with HCM absolutely avoid high-intensity sports in which exertion comes in bursts – like hockey. Fischer had to retire, and now works with the Red Wings in development.

In 1998 Chris Pronger took a slapshot in the chest, and collapsed on the ice. The puck hit him in the chest at a particularly vulnerable portion of the cardiac cycle – a window of about 30 milliseconds – causing him to briefly go into cardiac arrest. Pronger’s heart converted back to a normal rhythm on its own, and he didn’t have any lasting deficits as a result. Anyone who plays the karma card on this one can shut the hell up. Pronger may have been the king of the pests, but nobody deserves cardiac arrest. Seriously. Can it. Pronger’s incident didn’t preclude him from playing hockey because it was a freak accident that could have happened to anyone with exposure to high-speed pucks, and had nothing to do with his actual heart anatomy.

Peverley going forward…

Once Peverley suffers through all his cardiac testing, decisions will have to be made about his need for an ICD, and whether he’s capable of playing – or if it’s worth the risk. Meanwhile Jiri Fischer has reached out to him and offered his support, and NHL fans, players, officials, and anyone else with a TV and a heart are wishing Rich the best.