'Love of the game': How mini sticks destroy walls, create bonds

What's small, curved, and basically guaranteed to damage drywall, picture frames, and basement windows across the continent? Hockey parents know the answer.

"There was one occasion where I hit my brother a little too hard, a little away from the wall, and he put a big hole right in the wall," Panthers forward Matthew Tkachuk says. He's not recounting an epic family feud with his brother Brady, but rather an average day playing the childhood classic: mini sticks.

"We played all the time. My parents built us a mini mini-sticks rink in our basement with the plastic synthetic floor so we could just slip around. We put two nets at each end and there were boards on one side, so we always thought the most fun was hitting each other over the boards.

"My parents were like, 'Why are we going to fix this? You guys are just going to keep doing this.' So we just kept building a bigger hole and it was a fun part of the rink."

The Tkachuks got off easier than the McCarron brothers.

"My brother put my head through the drywall," says Predators forward Mike McCarron. "We got in a battle and he pushed me from behind and I went right into the drywall. My dad made my brother and I fix it."

Many have memories like that. Some aren't about demolition and are even heartwarming. "I played a lot of goalie and my mom would shoot on me, I think that was some of the most fun I ever had as a kid," Panthers center Steven Lorentz says. "Back then, I obviously would play all day with her if I could."

Others prove sibling rivalries never die. "There were a lot of tears from my little brother," Lightning defenceman Haydn Fleury says. "I think I won most of the games."

Not so fast, says younger brother Cale Fleury. "He for sure had an advantage being two years older, but I was more feisty than he was," says the defenseman currently in the AHL. "I'd say I had my fair share of wins, too."

From amateur hockey fans to professional athletes, everyone has a mini-stick story to tell. And in a world increasingly spent immersed in social media and video games, this offline pastime is hotter than ever. While Bauer won't release exact sales numbers, it says it sells "hundreds of thousands" of mini sticks each year. How did a lowly promotional giveaway transform itself into a full-blown part of hockey culture?

Mini sticks' early days

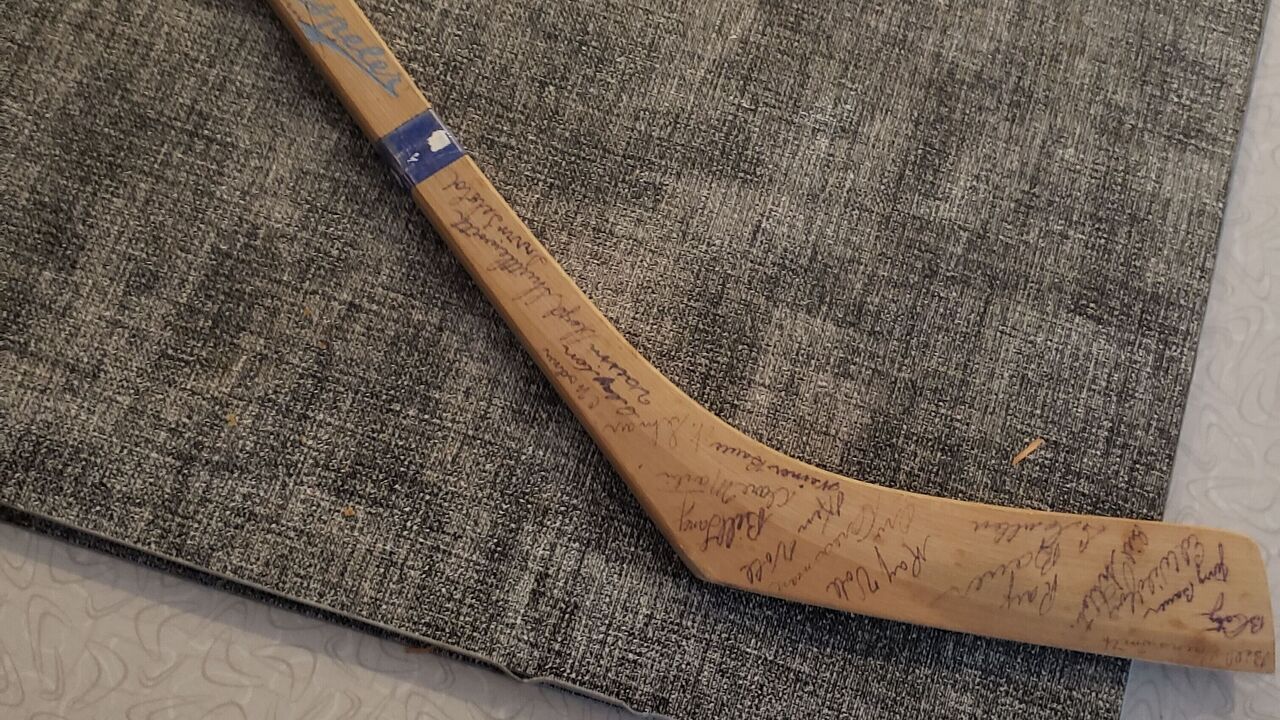

"They started back in the 1930s," says Mike Wilson, a Toronto-based sports memorabilia collector. Hockey might have taken a page out of baseball's book. Bat days, which Wilson says began in the 1900s, were once a common way to fill seats in the ballpark. "When hockey came along, they started doing the same thing but with a hockey stick," he says. Wilson's collection features sticks from the 1930s that are about 18 inches long with facsimile autographs and team logos along the shaft.

"In the '30s and into the '40s, it was just an easy way to collect signatures from a player and for teams to have," hockey historian and author Jon Waldman says.

Wilson owns one-piece sticks dating to the 1950s, but mini stick construction had evolved by the '60s. "I remember going to Maple Leaf Gardens back in the early 1960s and they gave away little sticks. There were two pieces of blade attached to the shaft. It wasn't very strong. There was a picture of the player on it. But they're very tiny. I played with them, but they broke all the time."

Using them to compete against friends and siblings evolved out of normal child's play. Wilson describes a form of knee hockey that was often played with whatever was available - broken hockey stick blades, coat hangers, or homemade wooden sticks. At a 1960s peewee hockey tournament in Quebec, Wilson says everyone got one-piece sticks with a little rubber puck from tournament organizers. It was a game-changer. "I don't think there was one kid at that tournament who didn't have a stick. I remember going back to the billet's house and playing in the basement on the floor with these things," he says. "It sort of evolved from there."

In the 1970s, teams leaned further into the marketing potential of mini sticks, using them to expand their team memorabilia. "It was usually around the commemoration of a particular player," Waldman says.

Wilson says that practice became increasingly prevalent through the 1980s. "But I would say they really took off in the '90s. Now they're part of the fabric of every kid growing up."

A Bauer representative said production of mini sticks is believed to have started in the late '90s, and there are only unproven theories as to what caused the exponential rise in popularity around this time. Wilson thinks it was a combination of their plastic construction and an uptick in minor hockey registration.

Another guess has to do with the memorabilia market. "It was in the '90s that, as the hockey-card market grew, everything around it grew as well," Waldman says. "When you look back at the sports-card world, it really started to pick up in the mid '80s but ignited as more companies came on board, especially in hockey in the early '90s. And with that, it sort of just took the whole memorabilia craze on this incredible journey. The hockey-card market didn't last very long as the hot piece. It sort of ran until 1993-94. But after that, a lot of the other memorabilia stuck around and teams started to see more value in having giveaway items.

"It became something that if you didn't have a program or you didn't have a ticket stub or a puck, a mini stick was one of the pieces that went hand-in-hand with a special event," he says.

While that might have been the collector's mindset, minor hockey athletes had a different vision for mini sticks - and that passion would catapult the collectible into a bona fide pastime.

Rules of engagement

The allure of playing mini sticks seems to be in its purity; it's a game of unorganized chaos with no purpose other than fun. "It's kind of almost all for the love of the game," Panthers forward Ryan Lomberg says. "It kind of gets to why we all started playing hockey - just because we love it. It's about having so much fun and just so many countless memories."

That said, certain aspects of mini sticks have become standardized, if not codified. One: location. A brief polling of professional hockey players showed a majority of mini-sticks games occur in one of two places. First, the basement.

"My parents didn't have their basement finished at the time. So it was just basically me and my brother duking it out on the cement floor downstairs. They put some plywood up so we didn't wreck the insulation in the basement," Haydn Fleury says.

"They were a gong show, so many holes in the walls in the basement," Oilers center Ryan McLeod says of battles with his brother Michael, who now plays for New Jersey. "The drywall was ruined, completely ruined, from body checks and slashing the wall."

Even NFL stars Travis Kelce and Jason Kelce have basement mini-sticks memories from their Cleveland-area childhood. "I remember the mini-stick arena, in the basement, that was carpet on cement, and we would run around on our knees," Jason Kelce said on a recent episode of their weekly podcast, "New Heights."

When games don't take place in the basement, the hotel hallway is most likely to serve as venue.

"That was the best part of minor hockey. People staying at the hotel probably didn't like it. But you got your team track suit at the start of the year, and the first tournament of the year you got holes in the knees from being on your knees playing mini sticks," Haydn Fleury says. "One of your teammates brought the net and all the boys brought their mini sticks and you played in the hallway."

"Every kid just knew after the game, win or lose, you were going to play mini sticks in the hallway with your buddies," Cale Fleury remembers.

Naturally, those hallway faceoffs have a way of perturbing hotel staff. "I remember we would be on a top floor and get in trouble because we were stomping and running around. So then we would move to the lobby floor but then still get yelled at by the main office in the lobby," says Saroya Tinker, a former professional hockey player and PWHL analyst. "We were definitely getting noise complaints and banging on doors with sticks and things like that."

To be sure, hotels have grappled with how to best manage the mini-sticks phenomenon. "We put (hockey teams) on certain floors - not on the top floor, but on the lowest floor," says Richard Wong, chief operating officer of Nova Hotels, a family-owned chain with 14 locations across western and northern Canada. When that doesn't work, Wong encourages his staff to find a dedicated space for hockey teams.

"'The good hoteliers are good about accommodating. It's about being flexible. We try to move (minor hockey players) into a meeting-room space where it's not constricted like it is in the hallways," Wong says. "The holes happen and things break, but I look at it as the cost of doing business."

Wong admits he has a soft spot for mini sticks from his own childhood. "For me, mini sticks equals fun."

Not every hotel manager is as accommodating or patient. Some have a no-tolerance policy on their website or that's bolded on reservation forms, and that might be due to one of the most recognizable elements of playing mini sticks. For a game passed down through generations almost exclusively by word of mouth, there's a surprising amount of continuity when it comes to how games are played, with the most enduring aspect being general lawlessness. No rules, just chaos.

"You can be on your feet or your knees. You can pull the goalie and play one extra offense and leave the net out there. You can body check, you can do all that stuff. The only rule was really there are no rules," Lomberg says.

"It was jailhouse rules," Oilers forward Evander Kane says. Although the Kane household did have one health and safety consideration. "I would play with my dad in the living room, and you get a little rough trying to push your dad around. There was a fireplace in the living room and if the ball went over there, we made sure no one went over there - we didn't want anyone to crack their head open," he says.

"Someone would take a ball or stick in the face or chop to the finger, but that's just stuff you have to live with and play through," Lorentz says.

As mini-stick technology has improved, that physical toll has only grown. "As we got a little bit older, they started coming out with fiberglass mini sticks. Bauer started coming out with their little mini versions of the sticks they use - to get kids into seeing those and using them early," Cale Fleury says. "I got high sticked with one of those at school in Grade 9 and it was actually pretty deadly. I have a scar on my eyebrow."

"We got the composite sticks and that just completely changed the game. It got pretty dangerous to be honest," McLeod says.

Obsessive habits typically reserved for on-ice equipment extended to mini sticks in the age before the new technology. Curving your mini blade was an art form, involving either boiling water or a gas stove's open flame.

"They used to just be little plastic things and I'd spend hours after school bending over the stove curving them. If I wanted to try a new curve, I'd grab another stick and I'd be bringing like seven or eight sticks in my backpack to recess to try out. I was all in," Lorentz says.

"I would just put mine right over the flame," Tinker says. "I remember the smell of burning plastic. The stick would end up being brownish-yellow by the end of getting the curve right."

Getting that curve right wasn't just about winning games; it was about belonging. "Growing up, we never were able to have new equipment or anything along those lines," Tinker says. "We definitely didn't grow up having the accessibility that many others did in hockey. So I think playing mini sticks, it was cool to just go pick up, like, a $10 stick and be able to curve it your own way and be good at hockey."

Mini sticks today

Perhaps as a counterbalance to kids' hyper organized and scheduled lives today, mini sticks are more popular now than ever.

"It's unbelievable, actually, we just can never get it right - as much as we ramp up the production and the forecast and everything, we're sold out," says Mary Kay Messier, Bauer's vice president of global marketing. "It always feels like the latest and greatest, hottest toy. Everyone's getting texts and emails, 'How do I get my hands on these mini sticks?' Kids are trying to trade, it's gone bonkers.

"People feel really nostalgic about mini sticks. Whether it's to give it to a young child when they first start, whether it's the kids who are playing in the tournaments, or kids wanting to hang them on their walls, it's just a part of hockey culture. Everyone has a mini-stick story, right?"

Messier adds that Bauer's popular Mystery Mini packs are part of how her team is trying to keep the product fresh. "We're doing more and more fun things like the Mystery Minis where you don't know what you're going to get. It's fun that it's kind of back to an old style of play that brings us all back and we can still pass that down to kids," she says.

Ten-year-old Willem Ostopowich is one of those kids. In his first year of Tier 1 for the Edmonton SWAT Huskies, his life revolves around hockey - and he has the stats to prove it: 10 goals and three assists in eight games. He recently fielded a call from theScore from the back of his family SUV on the way home from a travel tournament.

"We had about 15 guys playing mini sticks in the hotel this weekend," he says. "We had to keep finding new spots in the hotel where the manager wouldn't see us. We got caught five different times."

In the family's unfinished basement, Willem and his three younger brothers created their own league: the Mini Sticks Hockey League, or MHL, as they call it. Often their dad will join, or their 18-year-old neighbor.

"Sometimes I pretend I'm playing against Ryan McLeod," Willem says. He's broken a basement window during his imaginary matchups against his favorite NHLer; his dad is insisting he help with the repairs. And so far league play has resulted in one younger brother sustaining a facial injury that required stitches - the result of what appeared to be, on review by the MHL's Department of Player Safety, an accidental high stick. No disciplinary action was taken. As the oldest brother and de facto league commissioner, Willem's adopted the time-honored mini-sticks rulebook: "It's pretty much a free for all," he says.

The sum of all the parts - collecting tiny sticks, curving your own, running through hotel hallways, and challenging your siblings in the basement - is what makes the mini game great.

"Little things like that are where you fall in love with the game," Lorentz says. "When you're that age, you're pretending you're the next Sidney Crosby. Then you get to this league and now you're playing against him. It almost puts things in perspective. Those kids just love the game so much and it's so pure."

Willem says he uses mini sticks to practice his shot. But that's not what he likes most. His answer on that front isn't too different from what his NHL idols said: "My favorite thing is spending time with my friends, my brothers, and my dad."

Jolene Latimer is a feature writer for theScore.