40 years ago, a draft mishap triggered the worst era of Buccaneers football

The biggest mistake in the history of the NFL draft resulted in the selection of a damn fine professional football player. What made the error so noticeably ruinous is everything that happened afterward.

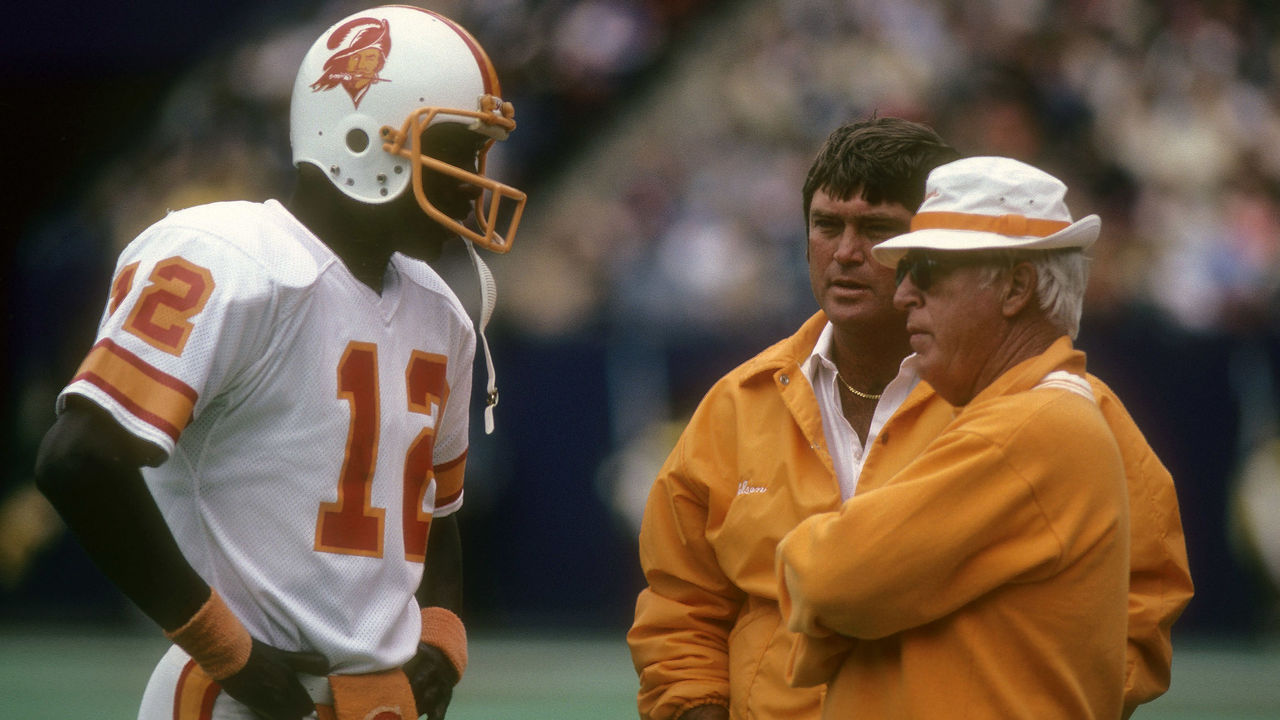

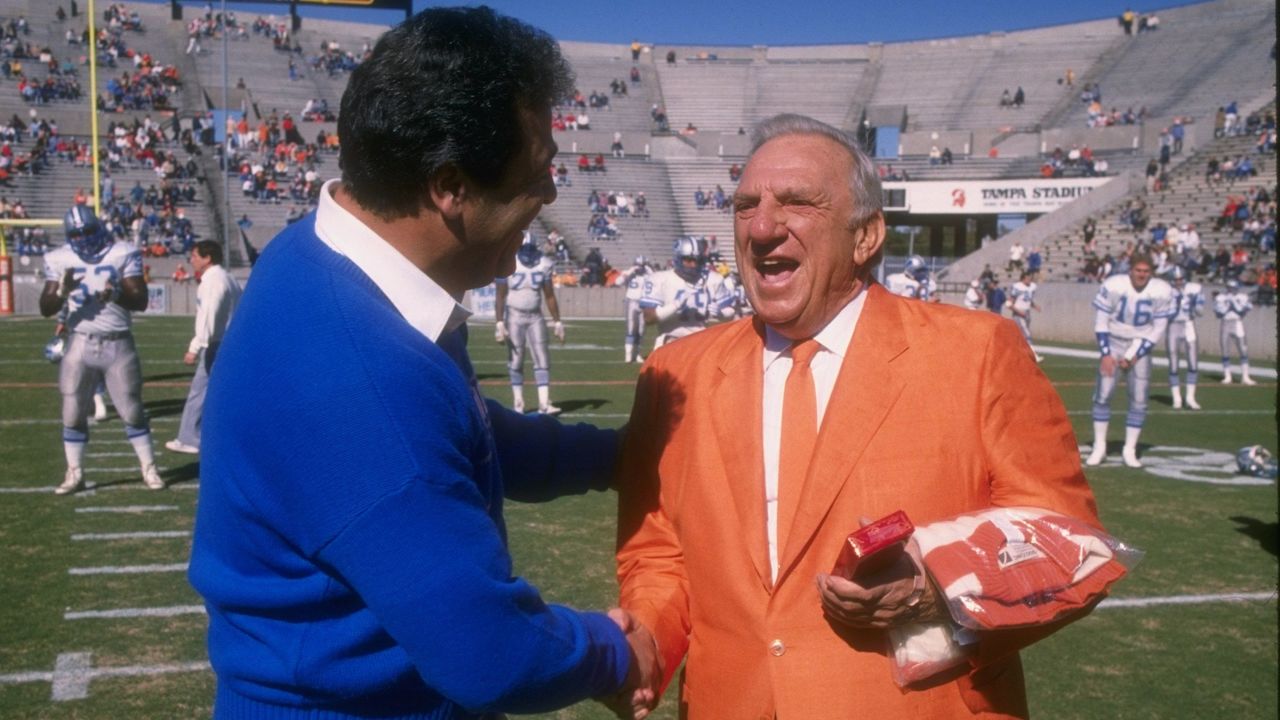

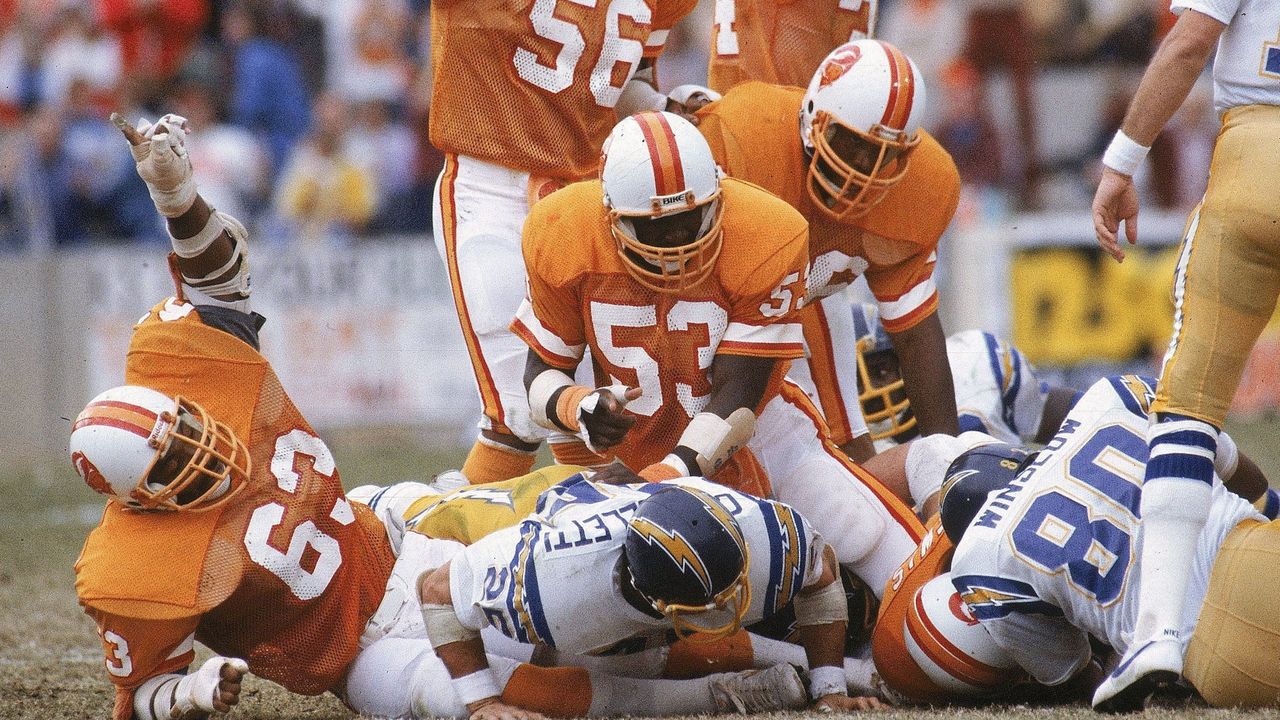

It was 1982. The Tampa Bay Buccaneers were coming off their second division championship in three years - an auspicious turnaround for a franchise that began play in 1976 and lost its first 26 games. The Bucs had a pedigreed head coach in John McKay and a promising young quarterback in Doug Williams. They had a future Hall of Fame defensive end in Lee Roy Selmon and a young outside linebacker bursting with potential in Hugh Green. They were primed to build a consistent winner, and had the 17th pick in the first round of the draft.

Then they picked the wrong player. Literally.

"Oh, Jesus Christ," then-Bucs director of player personnel Ken Herock told theScore in a telephone interview. "That story."

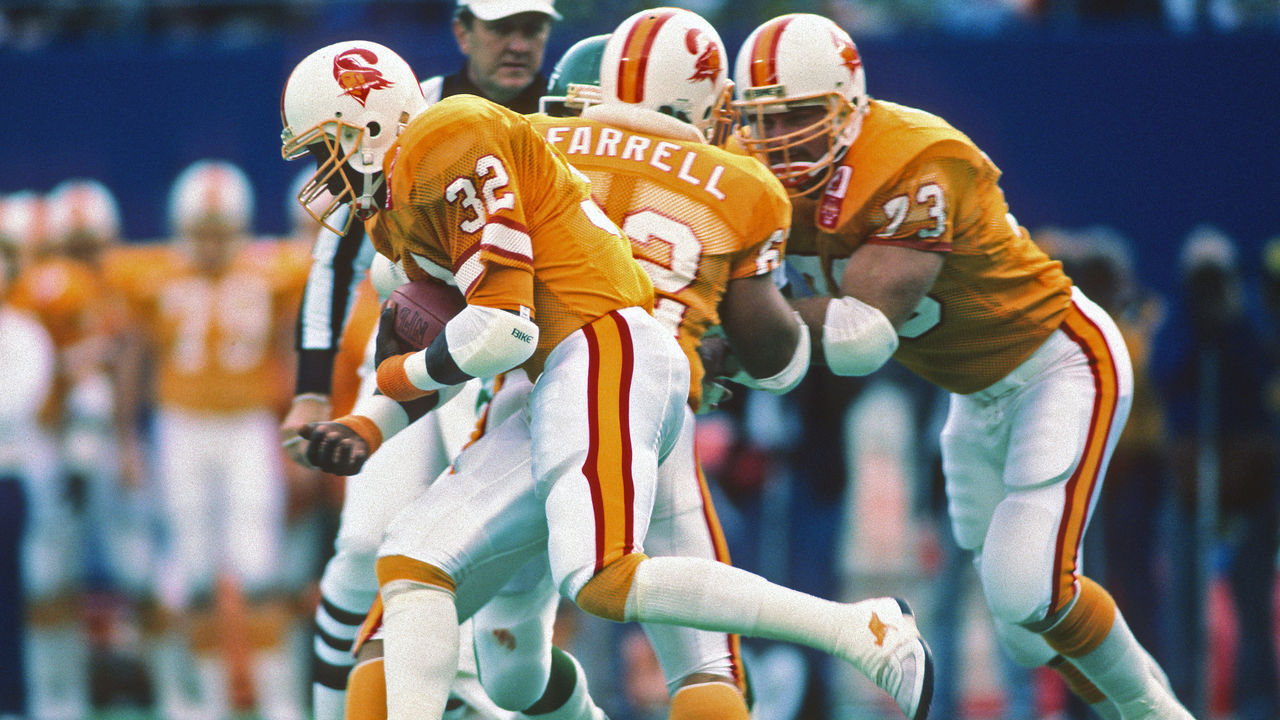

No, really: Forty years ago this week, Tampa Bay intended to select defensive end Booker Reese from Bethune-Cookman in the first round, only to mistakenly submit to the NFL the name of Penn State guard Sean Farrell.

Every team in the league has proven to be incapable of mastering the draft, and all 32 franchises have made a bushelful of rotten selections over the years. But a team that picked the wrong dude because it turned in the wrong name? Yup. It really happened. And somehow, for the Bucs, that's not even the worst part of how this improbable saga played out.

On draft day, the team's entire brain trust was back in Tampa. Their man on the ground at the New York Sheraton Hotel - the site of the draft - was equipment manager Pat Marcuccillo, whose job was to wait by the phone for the team's decision. He then would relay the name to the league to officially submit the pick.

Both Marcuccillo and Herock told theScore it wasn't uncommon in those days for non-football operations personnel like equipment managers or trainers to represent the franchise on-site at the draft. In fact, 1982 wasn't the first time the Bucs assigned the task to Marcuccillo.

"It was nothing like it is today," Marcuccillo, who now works in guest services at the San Francisco 49ers' stadium, told theScore. "Nobody had computers, nobody had a guy standing next to them if they want a drink of water. I had a black phone, and I had a desk."

With time winding down on the Bucs' 15-minute window to make their pick, Herock phoned Marcuccillo. As Herock told Sports Illustrated in 2014, he instructed Marcuccillo to write down the names of both Farrell and Reese. He also told him to sit tight as the team's brass debated which player it would ultimately choose.

Farrell was a two-time All-American at Penn State, where he played along an outstanding offensive line that also included future Hall of Fame guard Mike Munchak, who was drafted eighth overall that year by the Houston Oilers. Reese, the 1981 Black college player of the year, was much rawer: a 6-foot-6, 260-pounder whose athletic skills caught the eye of Bucs defensive coordinator Wayne Fontes and defensive line coach Abe Gibron.

"We thought we needed both of those players, but after we mulled it over and discussed it, the selection was to go with Booker Reese," Herock told SI. "So I told Pat, I said, 'Listen, Pat, you've got two names there.' I said, 'We’re not going with Sean Farrell, we're going with Booker Reese. Turn it in.'"

To this day, Herock doesn't know why he phrased it that way. His decision to mention both names proved to be fateful.

The Bucs draft room was gathered around a speakerphone; Marcuccillo was on an old-school telephone. As Marcuccillo told theScore, he was seated at a desk far from the dais, beneath an eave where a bunch of rowdy hometown New York Giants fans were situated. The Giants had the pick following the Bucs', and with a few minutes of Tampa Bay's allotted time remaining, those fans began to chant loudly and stomp their feet. They hoped the Giants would select Michigan running back Butch Woolfolk (which they did).

"You couldn't hear a thing," said Marcuccillo, who described how he had the phone pressed tightly against one ear and a finger jammed in his other ear, in a desperate attempt to make out anything Herock was telling him.

"There was about maybe two minutes, two and a half minutes to go. And he goes, 'Pat, write down Sean Farrell, guard, Penn State.' OK, Sean Farrell, guard, Penn State. And on my children’s lives, the next two words I heard - or next three words - (were) 'Turn it in.' I never heard 'Turn in Sean,' I never heard 'Turn in Booker Reese.' He said, 'Turn it in,' and that was the last name I heard, Sean Farrell. So I turned it in."

After the pick was announced, there was panic. Herock and at least one other person in the draft room told SI they remembered Marcuccillo being told to plead to get the selection rescinded. But Marcuccillo, who was not quoted in the SI story, told theScore that the idea was suggested, but the brain trust back in Tampa instead told him to stay put and keep quiet. Owner Hugh Culverhouse broached the subject with Pete Rozelle, according to Marcuccillo. As one might expect, this cartoonishly hopeless entreaty proved to be fruitless.

"I was upset," Marcuccillo remembered. "I thought for sure I was going to get fired."

Marcuccillo recalled Herock and McKay telling him everything was fine, and that he needn't worry. After all, the Bucs still had to get through the rest of the draft, starting with the second round.

The Bucs lacked a second-round pick, having traded it two years earlier to the Miami Dolphins for a pair of middling players. And as the first round wound down, Reese was still available.

"The D-line coach really wanted him," Herock told theScore, referring to Gibron, who died in 1997. "I said, if you really want him, I'll make a trade and go get him."

A Bucs assistant coach told the Tampa Bay Times years later that Gibron's enthusiasm for Reese had cooled by draft day. Marcuccillo, even now, remains convinced that either Culverhouse or general manager Phil Krueger initially wanted to draft Reese because he'd be easier to sign than Farrell, a notion that Farrell's agent, Marvin Demoff, dismissed in that SI story.

Whatever the motivation, the Bucs chose to double down on Reese. In an attempt to chase its error, Tampa Bay inexplicably traded its 1983 first-round pick to the Chicago Bears to nab Reese with the fifth pick in the 1982 second round (32nd overall). The 1983 draft was already shaping up to become one of the most talent-rich in league history, but that didn't stop the Bucs from pulling the trigger on dealing their top selection to acquire Reese, even after Reese tumbled into the second round.

It was the first in a series of poor decisions that would doom the Bucs franchise for the next decade and a half.

First, Reese turned out to be unfit for the NFL, in more ways than one. Then the Bucs lost Williams, their quarterback, to the fledgling USFL after the 1982 season because the notoriously cheap Culverhouse refused to meet Williams' contract demands. Williams maintained in his autobiography that the two sides differed by only $200,000, though Krueger was later quoted in a book saying Williams wanted to be the league's highest-paid QB.

Either way, the Bucs entered 1983 without a quarterback - and without a first-round pick in a draft that was stocked with premium signal-callers like John Elway, Jim Kelly, and Dan Marino, in addition to future Hall of Famers at other positions like running back Eric Dickerson, offensive lineman Bruce Matthews, and cornerback Darrell Green. Making matters worse, Tampa Bay chased its mistake again by sending its 1984 first-rounder to the Cincinnati Bengals for QB Jack Thompson, a 1979 first-round pick who failed to beat out Ken Anderson. Thompson lasted only two seasons with the Bucs and went 3-13 as a starter before losing his job to journeyman Steve DeBerg, who was also acquired via trade.

In the midst of all this, Herock left, too. All because of a dispute with Culverhouse over money.

"He just didn't want to pay me what I wanted, and so I had an option, and I went to the USFL," Herock said.

The team's problems kept snowballing from there. One of Herock's last moves with the Bucs was the selection of QB Steve Young in the 1984 supplemental draft of players who'd signed on with the USFL. Young joined Tampa Bay in 1985 as the USFL began to fall apart, but the team was such a disaster that Young was only able to win three games in two seasons before being traded to the 49ers - with whom he would go on to have a Hall of Fame career.

In 1986, the Bucs selected running back Bo Jackson with the No. 1 pick. A contemporary report indicated that after Jackson had dinner in Tampa with a group that included a handful of Bucs players plus Hugh Green, who was traded to the Dolphins in the middle of the 1985 season, Jackson chose to play baseball instead.

Many years later, Jackson told USA Today's Bob Nightengale he refused to play for the Bucs because he believed Culverhouse flew him to Tampa for a physical before reporting it to the NCAA as an infraction, in an attempt to prevent Jackson from playing baseball during the spring of his senior year at Auburn.

"I told myself, 'All right, if you screw me, I'm going to screw you twice as hard,'" Jackson told Nightengale. "If anybody else had drafted me, I would have gone, but I wasn’t going to play for that man.

"People thought I was crazy, but it was just morals. If you screw me over like that, and I'm not part of a team yet, just think what they'd do to me under contract. I couldn't do that. I needed the money. I was as poor as a Mississippi outhouse. I needed that money. But I couldn't play for that man."

Tampa Bay chose Heisman Trophy-winning QB Vinny Testaverde first overall in 1987, and he was gone three years later, only to find more success elsewhere. You get the idea. The Bucs were the league's never-ending laugh track from 1983 until 1996, wobbling aimlessly through 14 straight losing seasons, a stretch of futility in which they lost fewer than 10 games once. The Glazer family purchased the team in 1995 following Culverhouse's death and head coach Tony Dungy arrived the following year.

Ironically, even as the Bucs kept skidding into a ditch, Farrell - the player they drafted by mistake - developed into a legitimately solid player. But the losing - and the slapstick way the Bucs ran their operation - took quite a toll. By December 1986, as the team was nearing the end of a third 2-14 finish in four seasons, Farrell appeared at a booster club event at Disney World in Orlando and let loose.

"I know what I want this Christmas," Farrell said, with the Orlando Sentinel adding that he leaned forward for emphasis. "I want to get the hell out of Tampa Bay."

Asked where he wanted to go, Farrell replied, "I don't care where I'm going. I just want out. I want to play football for a number of years, but not if there is no fun."

Years later, in an interview with SI, Farrell provided specifics about the Bucs' shoestring approach. He compared the team facility to a "solid high school" building. He described how the team would bill players for any game balls they received and for the sweatsuits they wore during walk-throughs when it got a little cold outside. The soda machine required exact change. And because there was no on-site food being provided, players often hit the drive-through at a nearby fast-food joint for lunch after taping up for practice.

"All true stories," Farrell told SI. "It was ridiculous."

Herock told theScore the lack of on-site food operations was common in the 1980s, but Farrell noticed the difference when got his wish in February 1987 and was traded to the New England Patriots. There, catered meals were provided. Farrell spent three seasons in New England and also played for the Denver Broncos and Seattle Seahawks in what wound up being an 11-year NFL career. He later went on to work in financial services in the Tampa area and for an organization run by Culverhouse's daughter, Gay, that assisted former NFL players dealing with disability issues after their careers.

Reese's trajectory has been much different. He couldn't play, but he also was naive and ill-prepared for life as a pro athlete. One of the more famous anecdotes about his lack of guile involves what happened shortly after he signed his rookie contract. Reese went to a Tampa car dealership and attempted to purchase a vehicle for himself and his mother. He tried to pay for it all by handing over his $150,000 bonus check and asking for the change.

Reese also developed a problem with drugs and alcohol - at a time when the league (and society at large) was far less understanding about addiction and mental-health issues. In 2003, Reese told the Tampa Bay Times he began using cocaine in 1981, when he was still at Bethune-Cookman, and that he developed a habit that only worsened when he found himself with money and lots of time on his hands during the seven-week players strike in 1982.

It was never Reese's fault that he was selected under such absurd circumstances. But he had to bear the burden of expectations placed upon him. As he struggled to perform, self-doubt began to creep in. His use of alcohol and drugs worsened.

"It wasn't panning out," Reese told the Times. "I wasn't what I thought I should be. I kept wondering: 'Why am I not excelling?'"

After a drug-related arrest in 1984, Reese was traded to the Los Angeles Rams. His career in Tampa Bay lasted only 24 games. He went to rehab while in L.A., but was released after 11 games following a positive cocaine test. One last stint with the 49ers in the 1985 offseason ended after another positive test. That 2003 interview with the Tampa Bay Times took place at a Florida state prison, where Reese was serving time for a parole violation related to a 1999 drug arrest.

Sports Illustrated was unable to reach Reese for its 2014 story, with several sources telling the magazine they heard he was homeless and living in his native Jacksonville. theScore tracked down a number listed for Reese in that city, and while he didn't respond, his son, Michael, replied to a text message to say his father declined to comment.

"It was 40 years ago and he's moved on and has finally gotten to a peaceful place in his life," Michael Reese said in his text. "And speaking to him, he just wants to leave all that in the past."

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.