Race-norming isn't the only problem with the NFL concussion settlement

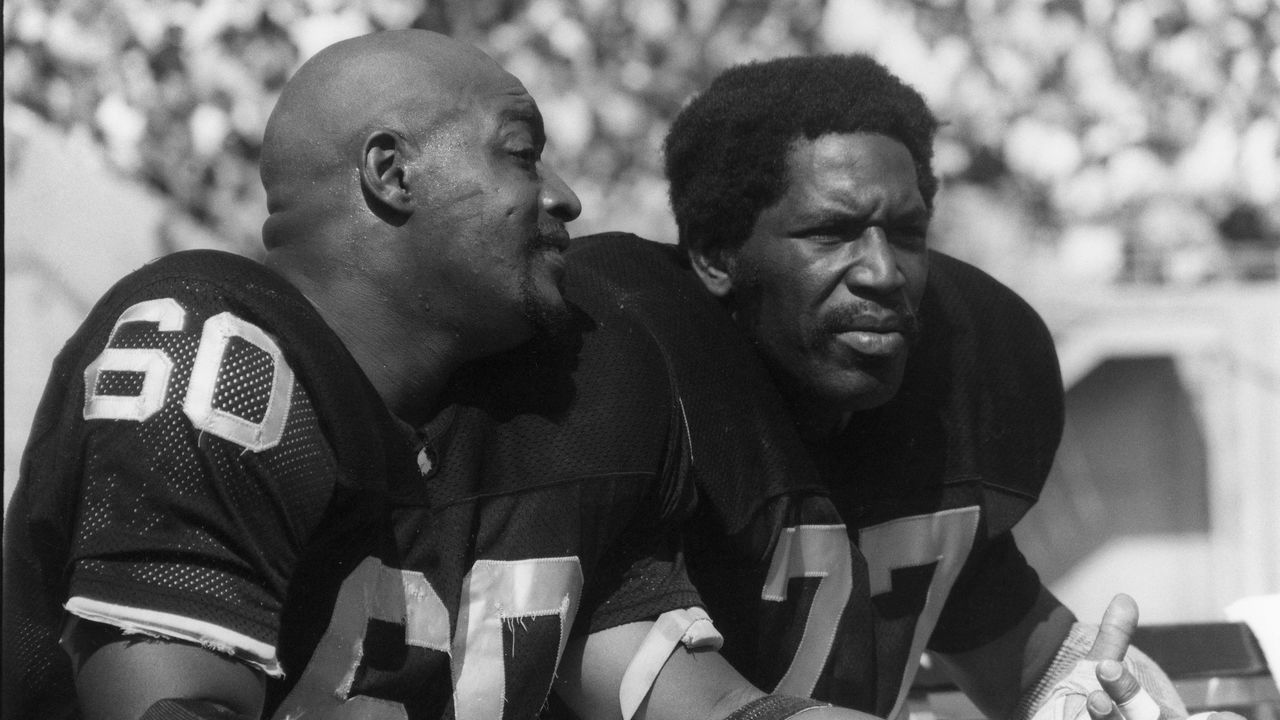

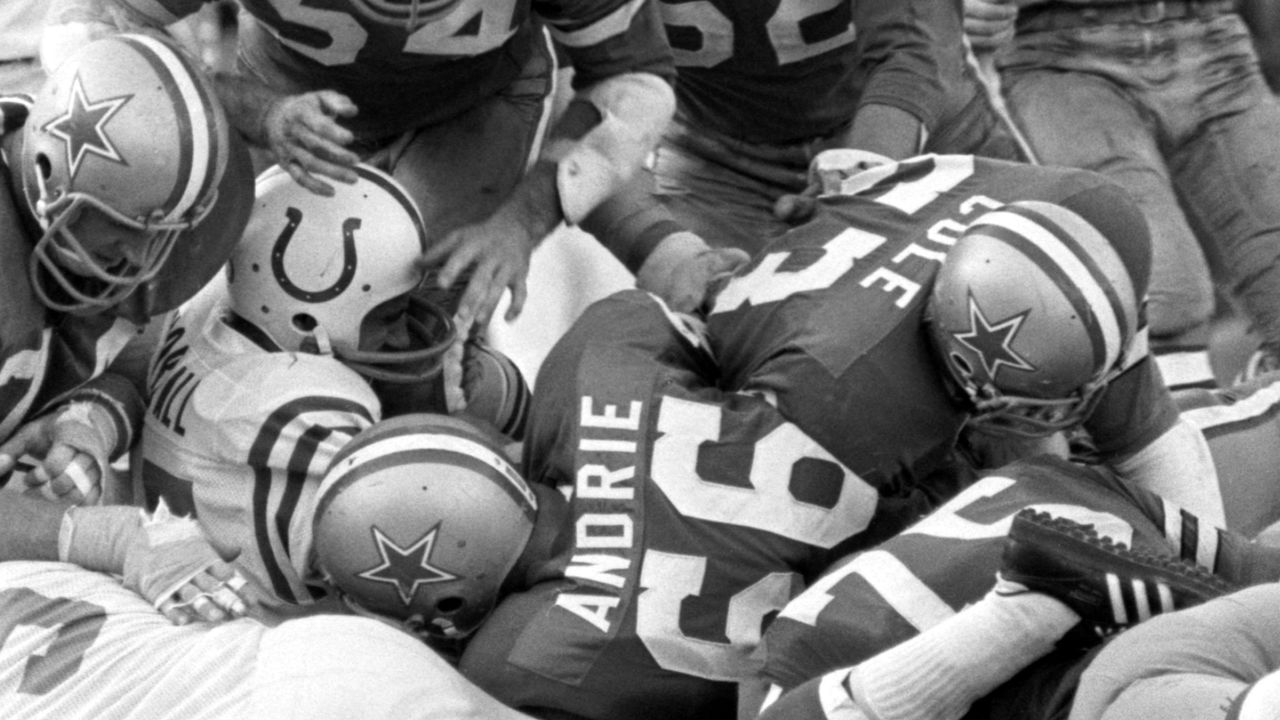

Before his death in August 2018 at the age of 78, George Andrie was diagnosed with dementia by four different doctors. Posthumously, researchers who examined his brain discovered he suffered from Stage 4 chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Yet Andrie, the ex-Dallas Cowboys defensive great, had his NFL concussion settlement claim denied not once, but twice.

After an appeal, Andrie eventually received a payout shortly before his death, though the amount was far less than the settlement's guidelines suggested he deserved. He only received an award because of the persistence of his daughter, Mary Brooks, who once shared with me the exasperating story of how she made it her mission to understand the excessively confusing claims process. Even after all that aggravation, Brooks still didn't know which settlement guidelines were followed to grant her dad's approval until a claims administrator explained it to her over the phone.

“They threw me a bone to shut me up," Brooks told me at the time. "They got to put it on their books they paid another claim. Which makes them look good."

The concussion settlement is back in the news because the NFL and the lead attorney for the players' side agreed last week to end the practice of "race-norming," a neuropsychological and actuarial practice that assumes Black people have lower baseline cognitive ability, thus making it more difficult for Black former players to prove they qualify for a payout.

What does this have to do with George Andrie, who was white, and therefore not subject to the depredations of race-norming? Just that indignities like race-norming are a feature of the concussion settlement, rather than a bug. It took a (since-dismissed) lawsuit filed by former players Kevin Henry and Najeh Davenport to make a headline story out of the way the settlement has been a disaster for many players. It also took some dogged reporting by ABC News, which has since shamed both the NFL and the lead players' lawyer, Christopher Seeger, into admitting the settlement's baked-in racial bias needs to be corrected after both insisted as recently as March that said bias didn't exist.

"We are committed to eliminating race-based norms in the program and more broadly in the neuropsychological community," the NFL said in a statement provided to the Washington Post.

The concussion settlement is a mass tort that was established to compensate a class of more than 20,000 former players who accused the NFL of denying and fudging the science surrounding brain injuries. It was finalized in January 2017; former players who are registered claimants have 65 years to file for a payout should they experience cognitive decline later in life.

Leave it to the NFL to manipulate a system designed to hold it accountable for manipulating players' health. The settlement has no financial limit, a fact that has caused the league to use the agreement's complex guidelines and inscrutable diagnostic criteria to aggressively fight potential payments. According to the latest claims report, more than $858 million in claims has been approved. That's obviously a lot of money, but the figure also reveals how deep the problem of former players with cognitive impairment really goes: The original settlement Seeger and the league agreed to - before a judge threw it out in 2013 - called for a cap of $765 million. And that $858 million covers just 40% of the 3,211 claims filed so far, with the remaining majority having been denied, withdrawn, or sent back for additional documentation.

In particular, the NFL has zeroed in on dementia claims, which are defined by the settlement in lawyerly rather than clinical terms. As a result, what the settlement considers early or moderate dementia is trickier to diagnose than ALS, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, or death with CTE.

Dementia sufferers can be lucid and sometimes appear to live outwardly normal lives, which the NFL has used to chip away at what it described three years ago in court papers as "deep and widespread" fraud within the system - an allegation that even Seeger sympathized with and one that led the court to appoint a special fraud investigator. It's true that some players, lawyers, and even doctors have tried to game the system. But while dementia accounts for 63% of all claims submitted, just 31% of those dementia claims have been approved.

"Nothing has changed, nothing's improved," Sheilla Dingus, the founder of the non-profit Advocacy for Fairness in Sports and a frequent critic of the settlement, told me. "But with the national climate and racial tension, when the race-norming came out, that finally got some attention."

From the outset, the settlement has been a mess. The thicket of the claims process includes a webpage with more than 300 Frequently Asked Questions, a legalistic morass that can be difficult for a player's family to parse, particularly if they lack the resources to hire a good lawyer. Unscrupulous actors have been accused of predatory lending. Unsuspecting families like Andrie's are frequently blindsided by liens that can eat into payments or even swallow them whole. Andrie's daughter told me it took weeks of phone calls to get three liens removed so her father could at last get paid.

Individual plaintiffs' lawyers representing thousands of former players have taken aim at Seeger for not being as aggressive in standing up to the NFL as many would like. Seeger has hoovered up most of the more than $100 million the settlement set aside for legal fees. The federal judge overseeing the settlement shot down most of these other lawyers' efforts to bring the court's attention to the way it was failing players, including Seeger's approach. Those rejected appeals certainly seemed justified when Seeger appeared to side with the NFL on the topic of race-norming in March. Responding to ABC's report that some doctors felt the settlement's recommended protocols were discriminatory, Seeger said he had "investigated this issue" and had "not seen any evidence of racial bias in the settlement program." You could practically hear the high-fiving from NFL headquarters.

Seeger only reversed course - shockingly telling ABC last week he was "wrong" and that he didn't "have a full appreciation of the scope of the problem" - after that same judge ordered him and the league and into mediation to address race-norming. But given the stakes, how could he not have noticed until now?

The settlement also featured a striking lack of transparency, with the NFL, the judge, and Seeger frequently huddling out of public view and without the input of other lawyers to hammer out many of the issues related to the agreement. It's noteworthy that Henry's and Davenport's lawyers have been granted the opportunity to intervene in the race-norming mediation.

That Seeger apologized, vowed to look into every claim to see where race-norming was applied, and said he'll work to ensure those claims get fixed is undoubtedly a welcome development. A lot of good can come from this, including a re-evaluation of the widespread use of race-norming in medical assessments that have nothing to do with football. But because of the way the NFL does business, and because it took this long for Seeger to finally come around on the issue, there's reason to be skeptical that many of the settlement's wrongs can be righted.

George Andrie wasn't race-normed. His family didn't need his settlement payout. His daughter told me she went public with her story to be an example for others, to shine a light on a deeply flawed system that seems designed to get players and their families to give up. Plenty of other players and their families desperately do need that money. Many of them are dealing with the physical and emotional fallout of degenerative brain disease from football along with substantial medical bills, and they've been reluctant to speak up because they fear jeopardizing their claims.

A stated commitment to equal treatment for Black players in the settlement is a start, but it ought to be viewed as just that: a start. For that commitment to mean anything, there has to be follow-through, no matter how much money it costs the NFL.

As former NFL running back Ken Jenkins said to the Washington Post last week, "I'll believe it when I see it."

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.