Why isn't one of the NFL's greatest pass defenders in the Hall of Fame?

Hall of Fame debates are a staple of sports arguments - whether a player's amassed the credentials to be honored among the best in their sport is prime fodder for discussion over a beer. We're spotlighting a collection of players who we believe either deserve the distinction but haven't yet been inducted, or don't quite measure up but had a great impact on their franchise or sport.

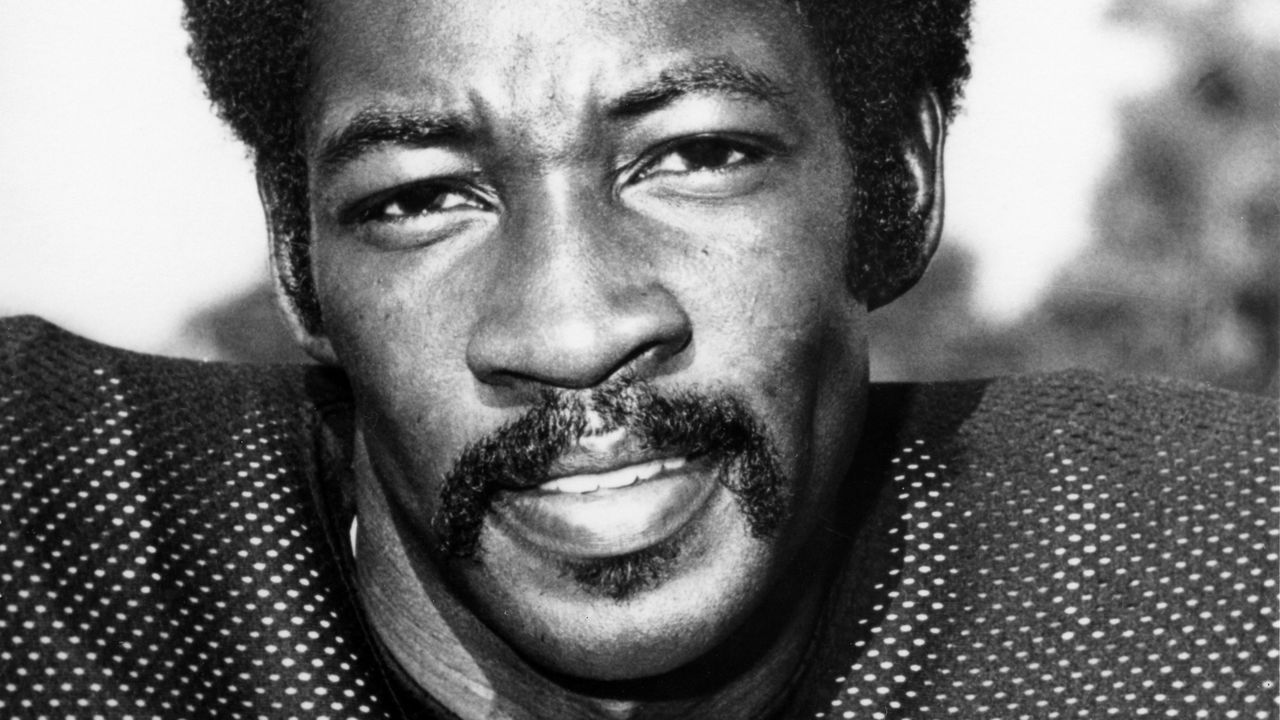

If ever there was a player whose career achievements prove that Hall of Fame selections are often nothing more than silly popularity contests, it's Ken Riley.

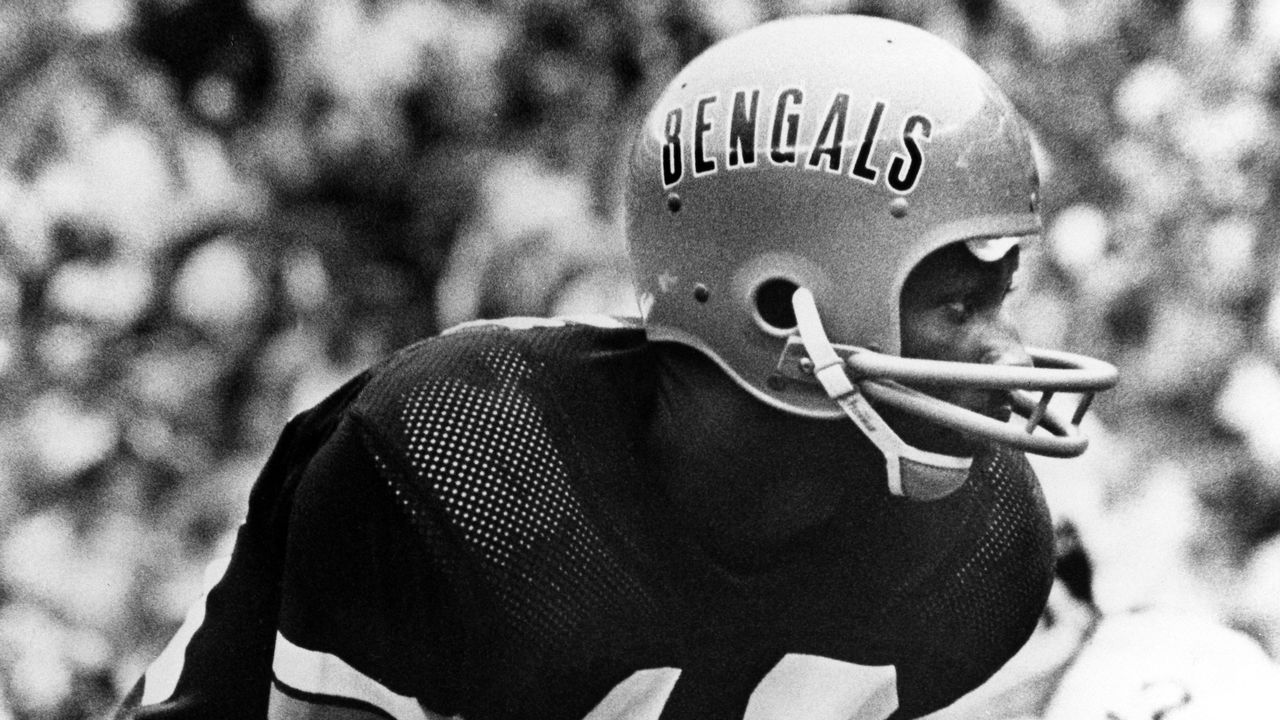

Riley spent 15 seasons in the NFL, all as a defensive back, all with the Cincinnati Bengals. This wasn't the era of the Bungles, either: Riley's tenure included five playoff appearances and a trip to Super Bowl XVI. He retired in 1983 with 65 career interceptions - fourth-most in league history at the time. Thirty-seven years have since passed, and Riley's now tied for fifth all time in picks. Yet he's never been so much as a finalist for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, let alone an inductee. All for unspoken reasons that are baked into the selection process, which has far less to do with merit than one might think.

"I think that the reason why he did not get more consideration for the PFHOF is that he was not a self-promoter," pro football historian Ken Crippen told me via email. "You need to have your name in front of the voters constantly if you want consideration."

Visibility and lobbying are a bigger part of the Pro Football Hall's procedures than one might think. Modern-era candidates are eligible for up to 25 years after their retirements, and beyond that there's a backlog of senior candidates, of which only one or two can be considered finalists in a given year. This can make it difficult for a player like Riley to get recognized, despite his obvious credentials.

"He was really smart, and had great quickness," Hall of Fame quarterback Dan Fouts told me. "Any ball that wasn't obviously on target, or was a little bit late, his quickness would always show up at that point. I think a lot of Ken Riley."

Hall of Fame wideout Charlie Joiner, who teamed with Riley on the Bengals and later played against him as a member of the San Diego Chargers, said Riley rarely dropped passes he was able to get his hands on. He also said Riley especially excelled at redirecting out of his backpedal to break on the ball.

"That's why he had so many interceptions," Joiner told me.

Football's only recently entered a quantitative era in which individual performances can be more closely scrutinized at every position. During Riley's time, it wasn't possible to gauge how he played against a particular pass-catcher or quarterback, or to determine how frequently quarterbacks threw in his direction (or away from him), or how well he played in man versus zone coverages, or how often he lined up in the slot or outside. Interceptions, however, are a traditional stat, and the Hall has long prized them as barometers for induction - but only to a point.

Riley's 65 picks rank second all time among cornerbacks, trailing only Dick "Night Train" Lane's 68. And of those in the top 10 all time at any position with 62 or more interceptions, only Riley, Charles Woodson, Darren Sharper, and Dave Brown are not in the Hall. Woodson won't be eligible until next year, and Sharper's name will likely never be called because he's currently in prison after pleading guilty four years ago to multiple rape charges. That leaves Riley and Brown, and Riley finished his career with three more interceptions than Brown.

"He compares favorably with anyone that I've coached," former longtime NFL defensive coach Dick LeBeau told me. "The statistics don't lie, and his are all on the table."

LeBeau can relate to Riley's struggle to get his due. He coached the Bengals' defensive backs from 1980-83, during Riley's final four seasons. But he's best known for having been the Pittsburgh Steelers' defensive coordinator from 1995-96 and again from 2004-14. During those two stints, Pittsburgh made four Super Bowls and won two titles. That's relevant because LeBeau was also a cornerback for the Detroit Lions who finally went into the Hall as a player in 2010 - nearly 40 years after he retired with 62 career picks, which is tied for third among corners, and 10th among all defensive backs.

"I think the fact that the Steeler defense was so good kept my name current, no doubt," LeBeau said.

Riley had no such direct avenue to recognition. After his retirement, he spent two years as an assistant coach with the Green Bay Packers before taking over as head coach at Florida A&M, his alma mater. He later served as FAMU's athletic director before finishing his professional career as the dean of students at a Florida high school. He remained out of the limelight, and he liked it that way.

"This is my personality," Riley told The New York Times' Samuel G. Freedman back in 2013. "It’s the way I was brought up - parents, grandparents, everybody. Let your work speak for itself and be humble."

Riley grew up in Bartow, Florida, where he attended a segregated high school. He was a quarterback and a Rhodes Scholar candidate at Florida A&M. He never played defense until he reached the NFL, until after the Bengals picked him in the sixth round of the 1969 draft. Cincinnati selected quarterback Greg Cook fifth overall that year, and head coach and team founder Paul Brown had no intention of allowing Riley to compete with Cook.

At the time, and for years afterward, it was common for NFL teams to insist that Black quarterbacks switch positions, owing to a longstanding prejudice that they were not capable of playing the position. Years later, Brown's son, Mike, who remains the Bengals' owner and team president, told the Cincinnati Enquirer that Riley "couldn't play quarterback in the NFL. He probably thinks today he could, but he really had no chance there and my dad immediately moved him over to cornerback."

The Enquirer reported that Riley laughed when he was told what Mike Brown said. "I think I could have played if given an opportunity, but the guy that we drafted that year was great - and that was Greg Cook," Riley told the paper. "He was just super." Cook was indeed a hotshot prospect, but his career was ultimately short-circuited by injuries.

Despite his production, Riley had a difficult time getting recognition even during his playing days. He led the league in interceptions three times, but he never made the Pro Bowl and only once was chosen as an All-Pro - in 1983, his final season, when he intercepted eight passes at the age of 36. Meanwhile, another Bengals cornerback, Lemar Parrish, who was taken in the seventh round in 1970 and finished his career with 47 picks, went to eight Pro Bowls. LeBeau chalked this up to Parrish having been one of the league's most prominent punt returners.

"The punt returners, they're splash playmakers, and maybe Kenny overall suffers a little bit because of that," LeBeau said.

Pro Bowl and All-Pro selections do help bolster a player's Hall credentials, even though they're highly subjective honors that also frequently don't go to deserving candidates. As a result, Pro Football Reference's Hall of Fame monitor tool doesn't think highly of Riley's Hall qualifications. Yet for all his humility, Riley recognized this incongruity, as he once explained to Crippen for a story in the National Football Post:

The system is all screwed up. A lot of times, there were guys who made the Pro Bowl based on what they did the previous year. Lemar Parrish and I are good friends. In 1976, I had nine interceptions and led the conference. I had three in the last game against the Jets. I will never forget it. Charlie Winters was my secondary coach. They took me out in the third quarter. He said that he didn’t want me to get hurt because, "There is no way that this time they would pass you up." Lemar (Parrish) was hurt half of the season that year. When they picked the Pro Bowl, they selected him, which I never understood and neither did he. I can't fault him, but the system is all screwed up.

Freedman's written that Hall voters have told him off the record that playing in Cincinnati hurt Riley since it's a small media market. A Hall voter confirmed this to me, on condition of anonymity. Not even the advocacy of former teammates like Sunday Night Football analyst Cris Collinsworth, or opponents like Steelers wideout John Stallworth - a Hall member himself - has worked to bolster Riley's case. Offensive tackle Anthony Munoz remains the only player in the Hall who played the bulk of his career in Cincinnati.

Riley's day may come someday, but he won't live to see it. He died June 7, at 72.

We mourn the passing of one of the greatest Bengals ever, Ken Riley (1947-2020). In 15 seasons with the team, Ken accumulated the fifth-most interceptions in NFL history and was selected as an All-Pro three times. Our thoughts are with his loved ones at this time. pic.twitter.com/e2AXAAi3Kw

— Cincinnati Bengals (@Bengals) June 7, 2020

Dom Cosentino is a senior features writer at theScore.