From Grizzlies star to G League boss, Shareef Abdur-Rahim sticks to his vision

Shareef Abdur-Rahim's NBA teams lost a lot more often than they won, but at peaks among the valleys, the retired forward positioned himself in the presence of greatness.

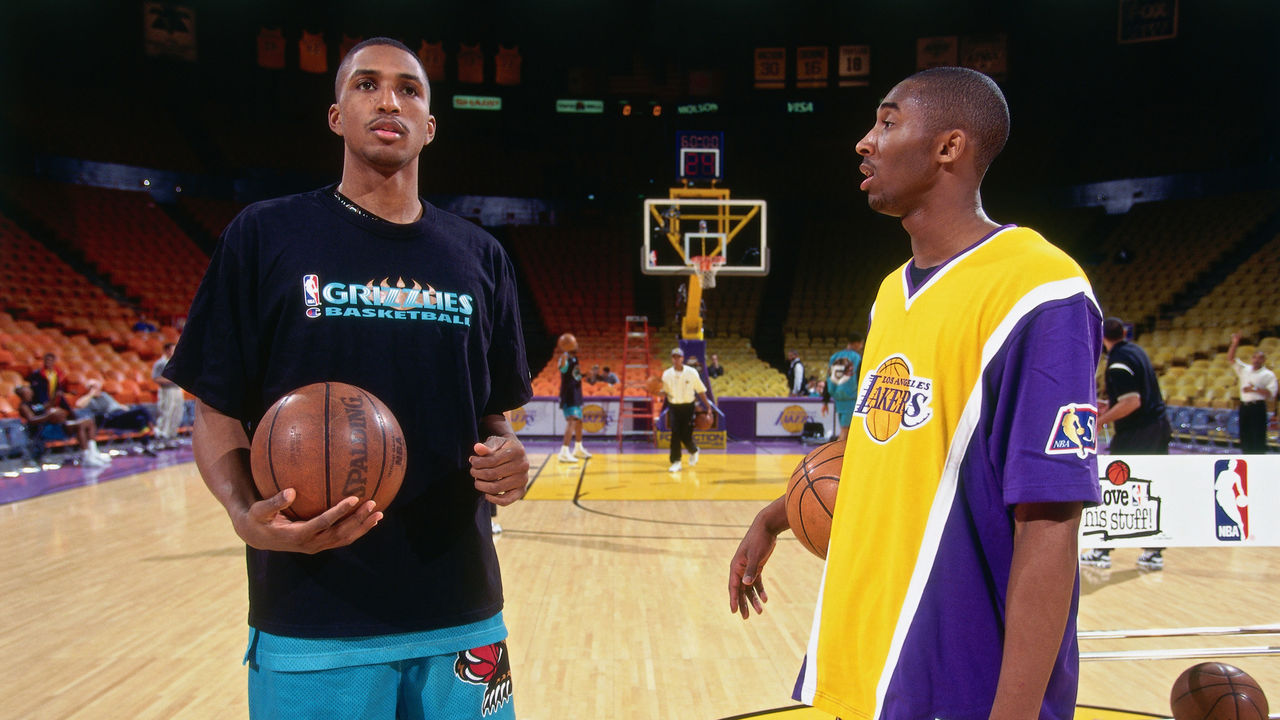

He was drafted third overall in 1996, two picks behind Allen Iverson and ahead of Ray Allen, Kobe Bryant, and Steve Nash. As a Team USA bench player at the 2000 Olympics, he saw Vince Carter, ball cocked overhead, vault a 7-foot-2 Frenchman and slam. At All-Star Weekend in 2002, his lone appearance on the stage, he wandered courtside during a lull in Philadelphia and shook hands with a childhood idol, Muhammad Ali.

Abdur-Rahim appeared in that All-Star Game as an Atlanta Hawk, representing his hometown club and his second NBA employer. First he tried his best to prop up the expansion Vancouver Grizzlies, who moved to Memphis after six seasons with an all-time win percentage of .220. Abdur-Rahim was Vancouver's offensive linchpin, the most reliable scorer in talent-strapped lineups from the moment he debuted as a one-and-done rookie out of Cal. The Grizzlies couldn't afford to be patient with his development, nor to insulate him from the strain of constant defeat.

"The team needed me to do a lot early," Abdur-Rahim said. "If there was a G League at that time, I think it would have been a place for me to gain confidence, to have different experiences, to play differently than what the team needed me to play. It would have been a benefit."

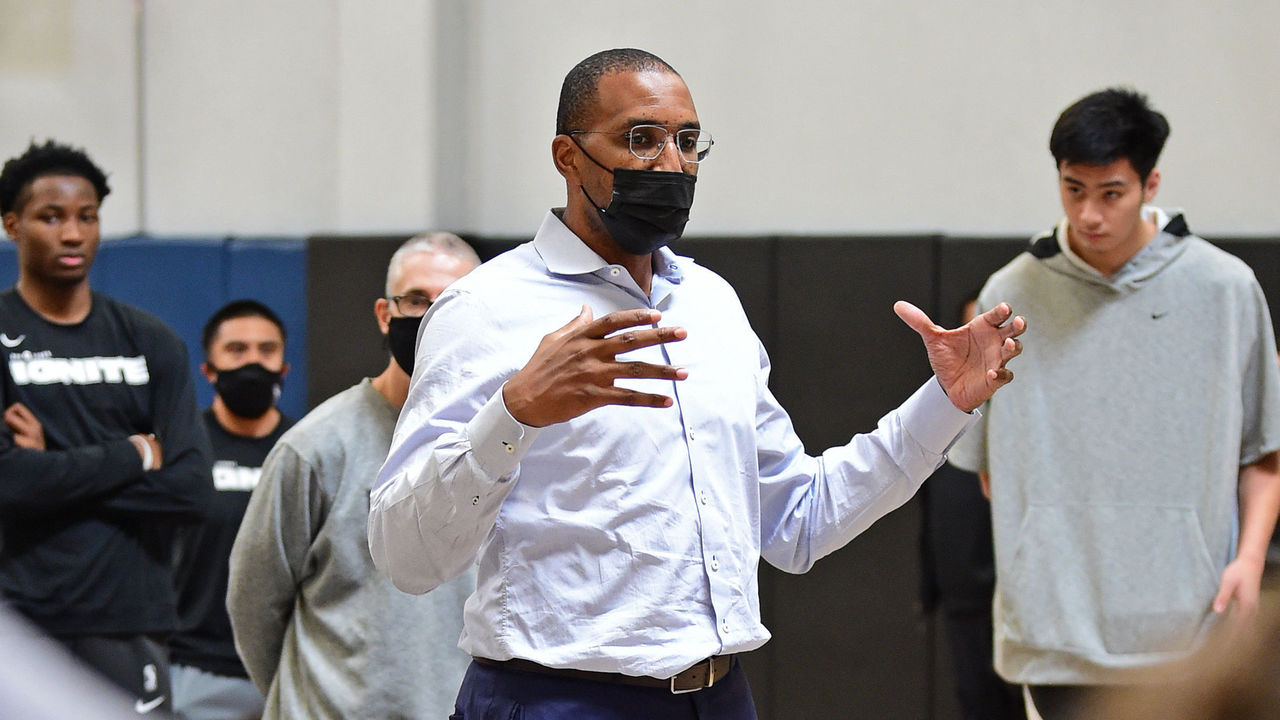

Abdur-Rahim mulled the hypothetical over Zoom this February in his capacity as president of the G League, the NBA feeder system that intends to weather COVID-19 by localizing its 2021 season at Disney World. The prospect incubator that didn't exist when he left Cal now connects directly to 28 NBA franchises. Eighteen G League teams are competing in the bubble, each of them striving to produce the next Alex Caruso, Duncan Robinson, Pascal Siakam, or Fred VanVleet.

Eyes are on the G League this season because of the Ignite, the new development squad whose best young players are angling to be drafted in the top five in 2021. For six-figure salaries, Jonathan Kuminga and Jalen Green signed up to pioneer this track to the NBA, a draft-year alternative for certain elite prospects who'd prefer to bypass college. Ten days into the 15-game bubbled campaign, the Ignite have shown they belong, starting strong at 4-2.

If Ignite program graduates wind up consistently populating NBA lotteries, some credit will go to Abdur-Rahim, who didn't create the pathway but did help land its first class of teenage standouts.

Such praise would bolster what already is a unique, fascinating basketball legacy. As a 12-year pro, Abdur-Rahim scored 20 points a night for five straight seasons, teamed with Carter and Allen to win Olympic gold, and once logged 85 games in a single regular season, the most in the NBA since the 1970s. He's presided over the G League since the beginning of 2019, making him a rare Black and Muslim leader of a major North American sports league.

To past teammates and coaches, it's fitting that the NBA has empowered him to lead off the court. They call him calm, curious, contemplative, and community-minded, not to mention universally respected. "You'll get no one to say anything bad about Shareef," said former Vancouver forward Grant Long. Who better to steer the G League and its aspiring stars through COVID-19?

"He's the type of personality who could be President of the United States," said Eric Musselman, the former NBA bench boss who coached Abdur-Rahim with the Hawks and Sacramento Kings.

"I've always viewed him as a builder. He's someone who's not afraid to take on tough challenges," said Amir Abdur-Rahim, Shareef's younger brother, relating this impulse to the origins of his NBA odyssey. "I'll never forget: When Vancouver drafted him, man, he was excited not only to be drafted. He was excited to go build."

Amir Abdur-Rahim is the men’s basketball coach at Kennesaw State, his first head job in a 15-year climb through the Division I coaching ranks. Shareef remains the only player he knows who was grounded as a kid for missing curfew to get shots up. They used to live in southwest Atlanta by the front of an apartment complex off Washington Road, and the court around the back of the place was well-lit.

"You could stay out there till midnight if you wanted," Amir said.

Amir is five years Shareef's junior, and he remembers his brother being preternaturally drawn to work, shunning video games and seeking dishwashing employment to chip in money for the family or for new shoes. That translated to hoops. The Abdur-Rahims volunteered at neighborhood events a few times a week, and he leveraged this for community-center court access, handling his assigned task before hustling off to shoot. At Wheeler High School - Jaylen Brown's eventual alma mater - Abdur-Rahim won a state title and twice was named Georgia's Mr. Basketball.

| Abdur-Rahim in the NBA | Seasons (12) |

|---|---|

| Vancouver Grizzlies | 1996-2001 |

| Atlanta Hawks | 2001-04 |

| Portland Trail Blazers | 2004-05 |

| Sacramento Kings | 2005-08 |

A starry freshman season at Cal got him drafted third in 1996, smack between Marcus Camby and Stephon Marbury and to a second-year team that never overcame its expansion growing pains. Abdur-Rahim was in Vancouver's starting lineup from the jump, a rare go-to scorer on replacement-level rosters that peaked at 23 wins. In his third season, he ranked top five in the league in usage percentage and points per game, keeping company with Iverson, Shaquille O'Neal, and Karl Malone. Without Abdur-Rahim, forward Pete Chilcutt said, "That team would have really struggled more than we did."

That Abdur-Rahim played in a mere six playoff games, all with Sacramento in 2006, belies how good he was in his prime. A regular 20-10 threat - he recorded 151 of them in his 830 career regular-season games - Abdur-Rahim was a "bucket-getter" from the post and midrange, said Ignite coach Brian Shaw, high praise from a longtime opponent who won three rings with Kobe and Shaq. To Musselman, from a defender's perspective, Abdur-Rahim was once among the league's five toughest players to guard - a nightmarish assignment because of his quickness, strength, handle, and range at 6-foot-9.

In today's NBA, were Abdur-Rahim to expand his shot profile beyond the arc, he might have been a walking mismatch capable of shuttling between three positions, picking and popping, and beating bigs off the bounce. In reality, he fared fine battling the likes of Tim Duncan, Kevin Garnett, Dirk Nowitzki, and Chris Webber. Against Ben Wallace's Detroit Pistons in 2001, Abdur-Rahim dropped a career-best 50 points without attempting a 3-pointer, one of six times that feat's been accomplished since he entered the league.

"He's definitely appreciated by guys who played in his era, who understood how tough it was at that particular time to play (power forward)," said 19-year NBA vet Jason Terry, Abdur-Rahim's Hawks teammate from 2001-04. "It was hard to be an All-Star in a league full of superstars, let alone they play your same position."

Recognition arrived in the form of his '02 All-Star nod and the run he got at the 2000 Olympics, where he played the fewest minutes but finished eighth on the undefeated U.S. in scoring. Those were the high points of a career otherwise defined by consistency, discipline, and professionalism. Abdur-Rahim fasted in-season during Ramadan and, with the Grizzlies, made time to pray postgame at the arena alongside teammate Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf. (Long, a veteran mentor in Vancouver, often joined them.) Terry recalls Abdur-Rahim's default mode on flights: dressed in suit and tie, thumbing the news and business pages of USA Today or The New York Times.

His diligence stood out, too. Some summers, Abdur-Rahim worked out at the same Atlanta health club as Long, refining his game with an offseason trainer before that sort of partnership was ubiquitous or even fashionable. So locked in was Abdur-Rahim, Adrian Wojnarowski once noted on "The Woj Pod," that his offseason standard was to train three times daily.

"I don't know if everybody does that," Amir said about his brother's old regimen. "I'm not sure if everybody is on the track in Georgia, in 85-, 95-degree heat in the summertime, running dashes on the football field."

Abdur-Rahim was still an offensive weapon when Atlanta traded him to the Portland Trail Blazers for Rasheed Wallace midway through 2003-04, enabling him and Theo Ratliff to dress in 85 games that season. Another quirk of his career: Abdur-Rahim played 744 regular-season games before he reached the playoffs, the second-highest such figure in NBA history. Within a couple of seasons, his knee faltered and compelled him to quit playing at 31.

| Abdur-Rahim post-NBA | Years |

|---|---|

| Kings assistant coach | 2008-10 |

| Kings assistant GM | 2010-13 |

| Reno Bighorns GM (D-League*) | 2013-14 |

| NBA VP of basketball ops | 2016-18 |

| G League president | 2019- |

*Now known as the G League

In retirement, Abdur-Rahim returned to Cal to get his sociology degree, earned an MBA at USC, and segued into the leadership sphere, starting with turns in coaching and management with the Kings. As a player, Abdur-Rahim liked to meet with team ownership to learn about their lives and career paths. Just as Long once counseled him in Canada, he's been a mentor to Brown, the Boston Celtics swingman who's advocated for racial justice and for their high school, Wheeler, to drop the name of a Confederate general. "Intellectuals in a field built on bravado," SFGate's Connor Letourneau called Abdur-Rahim and Brown in 2016.

In 2001, the year Vancouver dealt him to the Hawks, Abdur-Rahim founded the Atlanta-based Future Foundation to combat the cycle of poverty in his hometown. The initiative began as a small after-school program and now connects hundreds of underserved, mostly Black sixth- through 12th-graders to academic and extracurricular supports. Abdur-Rahim's sister Qaadirah was CEO of the foundation for 15 years, and he remains on its board of directors.

On his LinkedIn profile, Abdur-Rahim describes himself in part as a "social change agent." His personal website features quotes from Nelson Mandela on sports' capacity to unite and from Bill Gates on the importance of leaders empowering others. To Shaw, the Gates quote aligns with what Abdur-Rahim brings to the G League presidency: humility, approachability, and firsthand awareness of what young players require to develop.

"There are several different ways to lead," Long said. Across his 15 NBA seasons, he played with rah-rah types and also with teammates like Abdur-Rahim: "They say the most profound things in the most necessary moments."

Around the internet, Abdur-Rahim has written or otherwise reflected on his varied brushes with greatness as a player. He revealed some years back at The Players' Tribune why he doesn't appear in his draft class' group photo: He missed the bus from the hotel to the event. For an oral history of Carter's 2000 Olympic dunk, he told ESPN he uttered something unprintable when Vinsanity threw down on Frederic Weis. Meeting Ali was the peak of his '02 All-Star appearance; he'd long admired the heavyweight champ's swagger, courage, resilience, and boldness.

"He was bold enough to dance, to tell the world he was pretty, and to call himself the greatest long before he actually was," Abdur-Rahim wrote on his website last summer. "He had a vision for himself and his life - and he wasn’t afraid to proclaim that vision, even when he was the only one seeing it."

In 2020, as the U.S. dealt with COVID-19, protested racism and the police killing of George Floyd, and elected Joe Biden president, Abdur-Rahim blogged about the virtues of gratitude, empathy, adaptability, and voting. He drew macro life lessons from personal observations or experience. Ali was confident and outspoken, Abdur-Rahim wrote, and if we want society to be equitable and just, there's value in voicing the details of that vision aloud.

Early in the pandemic, he considered the link between school closures and systemic racism, outlining the resource crunch - from food insecurity to internet access - that many kids at the Future Foundation faced as they tried to learn at home. This was a symptom of structural inequalities that span generations, and to Abdur-Rahim, it spotlighted the need to act locally to try to drive broader change.

Last year, the Future Foundation raised $250,000 to alleviate this resource shortage, continuing the work that Abdur-Rahim initiated with the Hawks to honor his parents. His father, the late William Abdur-Rahim, was an imam who had his children devote their Thanksgiving mornings to preparing meals at Atlanta food banks or homeless shelters. The Future Foundation is headquartered on Washington Road, down the street from where Abdur-Rahim once hoisted all those shots after nightfall.

"The kids that they've been able to impact over the last (20) years through the Future Foundation, in a sense, they were kids like us," his brother Amir said.

"They didn't have the extra tutors or summer camp and things like that to keep them off the streets or out of trouble. Shareef had the basketball court. Luckily, he recognized, I think, at a very young age, something that he loved."

In that field, he has the chance to advance a different sort of vision. When Abdur-Rahim inherited the G League presidency from Malcolm Turner in 2019, he was tasked with building on the gains of Turner's term. From 2014 through 2019, the number of NBA affiliate teams swelled from 17 to 28. Turner was around in 2017 when the NBA introduced two-way contracts, and when the G League assumed its namesake letter to mark a partnership with Gatorade.

There remains room to grow in teams and in stature, though COVID-19 has complicated this pursuit. A Mexico City franchise, Capitanes, was supposed to debut alongside the Ignite this season but opted to postpone that plan a year. Similarly, Abdur-Rahim said, the pandemic slowed conversations about adding Blazers and Denver Nuggets affiliate squads, which would connect the G League pipeline to the entire NBA.

Short of that 30-for-30 status, the relationship between parent and minor league is still robust. When the NBA season tipped off in December, a record 45% of players league-wide had spent time in the G League, as had six head coaches. In quality and quantity, G League grads have proven the junior circuit a viable springboard.

At Disney World, the bubbled season continues through March 11, a year to the day since the pandemic initially paused the NBA and a few months shy of 25 years since Abdur-Rahim was drafted. Over Zoom, he listened to a partial list of his league's most celebrated success stories - Caruso, Kendrick Nunn, Spencer Dinwiddie, Lu Dort - and said their ascent should inspire the next batch of up-and-comers, be they unheralded or ballyhooed.

To those players, he offered one more lesson.

"If you see it, you can be it," Abdur-Rahim said. "You have an example of guys who have started where you are and risen to the top."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.