'Gonzo!' It's been 25 years since Jordan aired out 3 home runs in Double-A

Stranded on the mound against the Birmingham Barons, sweating out the anguishing interlude of an opponent's home run trot, Jeff Ware rued the fastball he'd just left dangling over the plate - a blunder, unbeknown to him, that would soon set him on course to reach the major leagues.

On Aug. 8, 1994, Ware was a 23-year-old Toronto Blue Jays farmhand enduring the first month of an unpleasant comeback from shoulder surgeries that had sidelined him for nearly two years. His return to the Knoxville Smokies' rotation had clarified his predicament: He was healthy enough to get rocked by Double-A batting every five days, but he wasn't sure if his right rotator cuff would withstand the strain. It made him reluctant to throw as hard as he once did.

It took the ignominy of a light-hitting rookie taking him deep for a three-run blast to relieve Ware of that concern. Feeling angry, he started to uncork the ball with his usual zeal. Knoxville's radar gun confirmed it - his pitches from that point on were a few miles per hour faster.

"After that day, I knew that I could go back to my old velocity," said Ware, who rebounded the following season by excelling at Triple-A before earning a September call-up to the Blue Jays.

"It gave me confidence. There were some things in there that were really good that came out of it," he added. "Besides the fact I was facing Michael Jordan, which is pretty cool in itself."

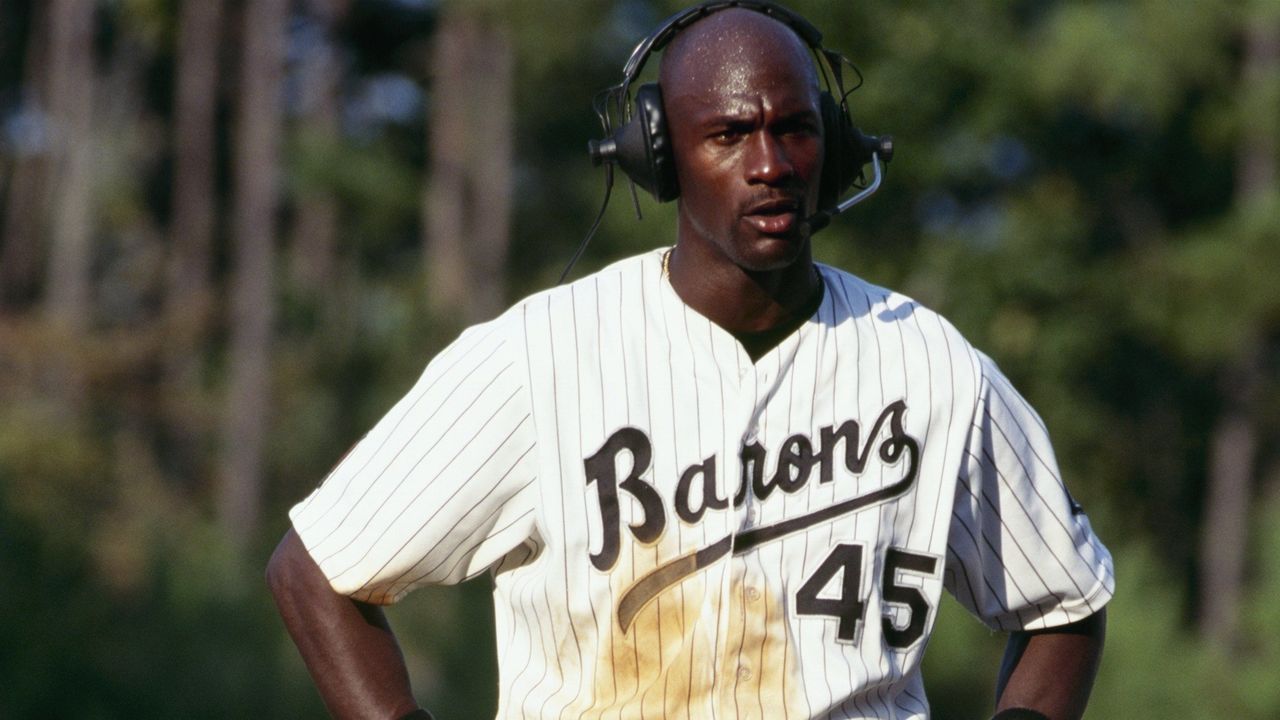

This baseball season marks 25 years since Jordan, at the time the reigning MVP of three straight NBA Finals for the unstoppable Chicago Bulls, relinquished his stranglehold on the Larry O'Brien Trophy to sign with the Chicago White Sox. The details of his spring and summer in Birmingham, Ala. - the scathing Sports Illustrated cover that urged him to quit; the bus trips across the Southern League on the chic Jordan Cruiser - made for a riveting second act in his sporting life, even if his .202 batting average doesn't quite jump off of his Baseball Reference page.

The story of Michael Jordan, left fielder and No. 7 hitter, is mostly about His Airness, of course, but it also features an important cast of extras: the lower-wattage minor leaguers who competed with and against him in 1994. For many of those players, this unlikely convergence with celebrity was a highlight in a career that didn't progress much further - a quirk of playing baseball decently well at a time when Jordan got bored of dominating on the hardwood.

Even in such a big group, Ware is in select company. Jordan stroked 88 hits for 51 RBIs in 127 games with the Barons that season. He also stole 30 bases, the second-best mark on the team. But he only tagged three pitchers for home runs: Kevin Rychel, Ware, and Glen Cullop.

The timing of Jordan's three homers - he hit them on July 30, Aug. 8, and Aug. 20, 1994 - serves as a useful illustration of how he improved in the batter's box during his rookie year. Pitchers tended to attack him inside with heat, hoping to shackle his long arms and capitalize on the rustiness of his swing. (A full 13 years elapsed between Jordan's last high-school at-bat in North Carolina, at age 18, and his first with Birmingham.)

Jordan hit just .165 in May 1994 and then .185 that June, but once he caught up to the speed of Double-A heaters and gave himself a fighting chance against breaking pitches, he started pounding balls to the gap with some regularity. By mid-July, Barons personnel believed he had a real chance to go yard.

When Jordan skied his first homer to left-center field in Birmingham's Hoover Metropolitan Stadium - with his wife, his mother, and two of his siblings watching from the stands - the milestone was special for plenty of reasons. It came in his 100th game, one day before what would have been his late, baseball-loving father James' 58th birthday. The opponent was the Carolina Mudcats, a Cleveland Indians affiliate based in the same state as his hometown.

Earlier that game, Jordan had twice belted balls to the warning track. In the eighth inning, Rychel's 2-0 fastball proved to be the pitch he'd been awaiting. "Gonzo, Jordan! He's done it!" Barons radio broadcaster Curt Bloom exclaimed as Jordan rounded the bases, before falling silent on the mic in deference to the roar of the crowd.

"As a broadcaster, trying to treat him like everybody else, I didn't want to make (his home run seem) as if it was God's miracle," Bloom said from Birmingham, where he still calls Barons games. "I didn't want to go, 'Wait a minute - this is a miracle and he was blessed.' No! He worked for it, and he did it."

Nine days later, in the third inning of a home date with the Smokies, injured Barons infielder Chris Snopek joined Bloom on air to tell a story about Rogelio Nunez, a Dominican catcher who faced off with Jordan in frequent pingpong matches - and whom Jordan paid $100 whenever Nunez learned a new English word. Snopek was soon interrupted by Ware's misplaced fastball, which Jordan bashed beyond the wall in the same direction as his first homer.

Difficult as the hit was to give up at the time, Ware mustered the nerve to approach Jordan in left field during batting practice the following day. "Man, why'd you want to take me deep?" Ware joked, shortly before asking the budding slugger to autograph two baseballs.

"Which was a little embarrassing, but heck, why not?" he said.

Although the Barons struggled in the standings with Jordan in the fold, finishing last in their five-team division, his third homer came in an emphatic 12-4 win over the Chattanooga Lookouts. Jordan's final mark was Cullop, a 6-foot-7 reliever who'd previously been a standout Division III basketball player.

Like Rychel, who was 22 years old when he pitched against Jordan and 24 when he retired from the game after topping out at Triple-A, Cullop's career didn't last especially long. He was 23 and playing for the High-A Winston-Salem Warthogs when, in May 1995, an opposing pitcher knocked him unconscious with a kick to the chin in the midst of a nasty bench-clearing brawl.

Cullop, who was hospitalized with a concussion, a broken jaw, and five lost teeth, didn't play pro baseball after that season. These days, he works at a chemical company in Tennessee, his home state, while Rychel is an executive at a chain of taco shops based in Texas. (Cullop and Rychel didn't reply to interview requests. Jordan's publicist, meanwhile, said he was unavailable to relive his baseball glory days.)

In the years after MLB's 1994-95 players' strike motivated Jordan to return to the NBA, Ware followed a different path out of the Southern League. His 3.00 ERA and 7-0 record with the Triple-A Syracuse Chiefs in 1995 got him promoted to the Blue Jays, for whom he pitched in 18 games over two seasons. He's now the Jays' minor-league pitching coordinator, overseeing the development of young hurlers throughout the organization.

A quarter-century on from his brush with rock stardom, Bloom can still recall - without prompting - the order of the three teams Jordan homered against: "I can't remember to bring home the tomatoes, but I can remember (that)." And, having witnessed Jordan's progression at the plate firsthand, he thinks his season should be remembered as a resounding success.

Ware is inclined to agree.

"For a guy who hadn't played baseball since, what, maybe high school, to step on a Double-A field and do what he did was pretty darn impressive," Ware said. "Not just to put the ball in the play, but to get the barrel on the baseball - to hit a couple of homers like he did."

Nick Faris is a features writer at theScore.