Relationships form the heart of this book about pitchers and their craft

Tyler Kepner's love affair with Steve Carlton dates back almost four decades.

Kepner was 6 when he attended his first game, which just happened to be Game 5 of the 1981 National League Division Series between his Philadelphia Phillies and the Montreal Expos. Steve Rogers outdueled Carlton for a 3-0 Expos win that ousted the defending World Series champions.

Kepner grew up to become the New York Times' national baseball writer and the author of the new paean to baseball's best pitchers, "K: A History of Baseball in 10 Pitches." He'd later interview Rogers for the book.

"I got to speak to the pitcher who vanquished my dreams," he said.

Baseball became Kepner's greatest passion and his life's work. His book can be seen as a primer on the history of pitching, but it's really a story about relationships: the ones pitchers have with each other, with themselves, with their catchers, and, most importantly, with the ball.

Kepner's relationship with the sport was cemented in 1982, the season after his first live game. "The baseball world opened up to me," he said. He met the Phillie Phanatic at a mall, and some of the Phillies themselves at a Chevrolet dealership. Fireworks nights remain vivid, nearly four decades later.

"People were going down to the field to watch," he said. "How can you not want to go on to the field? The feeling of being on the same field as Steve Carlton, Mike Schmidt, Tug McGraw - that was magic. I've tried to always remember it's a real privilege to be on an MLB field and walk among those guys."

The seeds of his career in journalism were planted almost as early. He wrote to David Montgomery, an old army reserves buddy of his father, who started in the Phillies' sales and marketing department and eventually bought the team with Bill Giles in 1981. "Mr. Monty," the beloved team chairman who died this month, came back with a whole stack of tickets.

In the eighth grade, Kepner used his career-day assignment to shadow Montgomery at the ballpark. Kepner saw how it all worked - every department of the organization. He got to look behind the curtain at the symphony that is a Major League Baseball game. For the first - but not the last - time, he set foot in a press box.

"It was just a blast," Kepner said. "One of the greatest days of my life, really."

Two years after that career day, he started KP Baseball Monthly magazine, inspired by famous Philly scribes Jayson Stark and Bill Lyon. He was 14 years old, and the Phillies issued him a field pass. He was in clubhouses by the time he was 16. Even got to go to Baltimore to do some road games.

KP Baseball Monthly folded during the MLB strike summer of 1994, with 64 issues in the bag. But Kepner's journalism path continued at Vanderbilt University, where he became sports editor of the school newspaper. After graduation and stints covering the Angels and Mariners in their local markets, he was scooped up by the New York Times. He started on the Mets' beat, switched to the Yankees, and is now the paper's national baseball writer.

"Baseball," Kepner said, "from the moment I stepped onto the field at fireworks night, I always wanted to be around it."

Kepner played too, of course. He once threw 12 innings on the Fourth of July, he says. He made it to his high school's varsity team, though he didn't see much time.

Of all the positions in all of sports, pitching can be the most humbling and most humiliating. As the book shows, for a pitcher who can deliver a devastating curve, a swooping slider, or a crafty changeup, it all begins with hope and doubt. And a good pitcher will search for something - anything - to get the job done.

Kepner learned that from knuckleballer Charlie Hough, who managed to stick in the big leagues for nearly a quarter of a century after learning to throw the pitch in spring training 1970.

"One little quote from Charlie Hough, almost a throwaway line: 'If you want to compete, you find something,'" Kepner said when asked for his favorite quote from more than three years of reporting for the book. "That's what these guys all do. They have to find something. You've got to find a way to be out there and hang. Hough, he found the knuckleball."

Years later, when Hough was pitching for the Los Angeles Dodgers, he spotted a precocious boy in the left-field stands at Candlestick Park in San Francisco and tossed him a ball. A knuckleball, of course. The kid threw one back, and Kepner reveals the kid was Tom Candiotti, who went on to spend 16 years in the majors as a purveyor of the game's most baffling pitch.

Nuggets such as those tell the story of pitching's progress through time - tricks of the trade passed on like folk tales through generations of players.

"I've seen the way pitchers talk shop, and I've told enough stories to realize these guys learn things from other guys," Kepner said. "To be able to travel up the tree like that was fun. It's almost like a trade tree. Johnny Podres throws changeups for the Dodgers, becomes a coach, and coaches Frank Viola, who throws changeups for the Twins and becomes a coach, teaches Noah Syndergaard with the Mets. That was really fascinating to trace."

Kepner started the book process with a rough outline of the 10 pitches that have perplexed batters for a century and a half: fastball, curveball, sinker, slider, changeup, cutter, splitter, screwball, knuckleball, and spitball. For each pitch, Kepner talked to dozens of guys who made the pitches special, and found almost all of his subjects were "really willing and happy to explain their craft."

The book covers Nolan Ryan on his blazing fastball and Clayton Kershaw on his curve. Bruce Sutter sings about his splitter and Mariano Rivera converses about his cutter.

"I started with a list of every pitch and then all the masters I could think of offhand," Kepner said. "That gave me a framework and a long list of targets. My baseball travels put me in the position to talk with many of them in person. It became a scavenger hunt."

Some, such as Mike Mussina, were easy to find. Kepner spent hours sitting down with the former Yankees and Orioles ace who, like Kepner, hails from Pennsylvania. Kepner appreciated the chance to interview older greats such as the Brooklyn Dodgers' Carl Erskine, who threw two no-hitters in the 1950s.

"He's in his 90s, and still so with it and such a great storyteller," Kepner said. "He told me what it was like to meet Three-Finger Brown. To talk to someone who has seen (Brown's) mangled hand - that was spellbinding."

There were white whales he couldn't land. He rues not getting the chance to speak with Tom Seaver before the legendary Mets and Reds hurler retreated from the public eye because of dementia. Whitey Ford and Sandy Koufax proved elusive. If it wasn't for a conference call for a golf tournament, he might have missed out on Gaylord Perry.

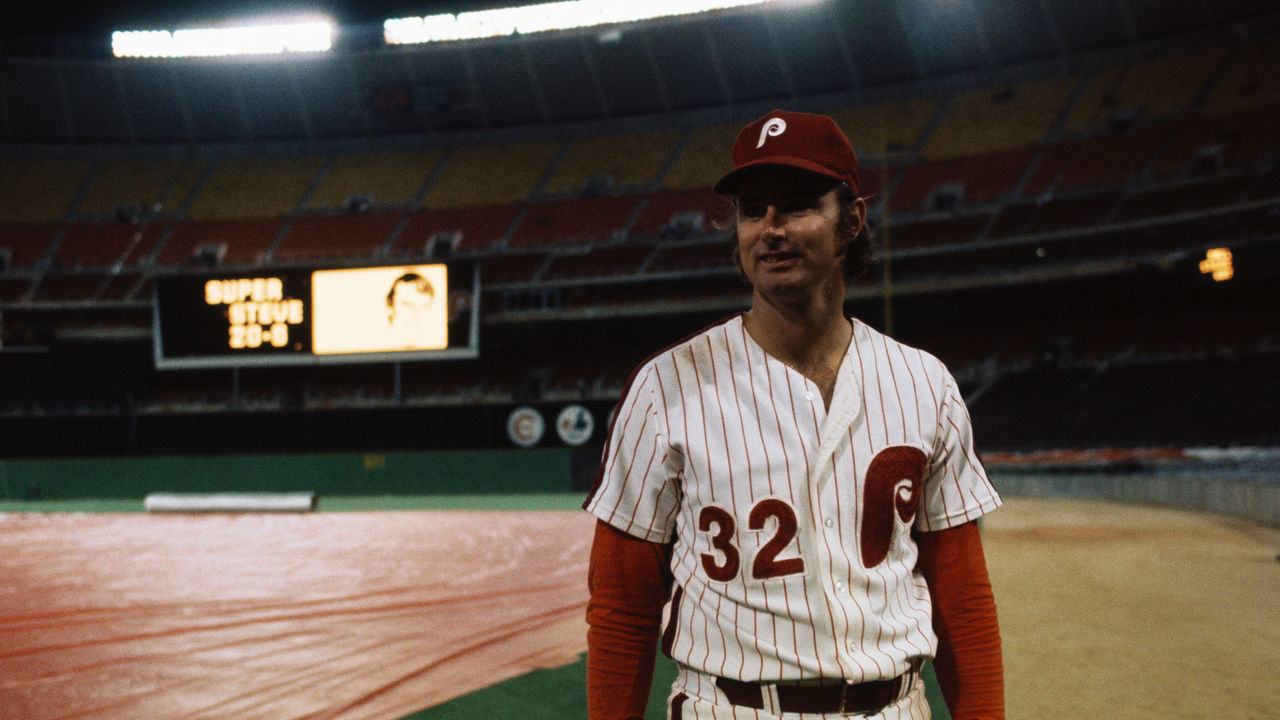

His best get? His idol, the ornery Carlton.

"My baseball hero, well-known for not talking to the media," Kepner said. "From a personal standpoint - one of the best, first to win four Cy Young Awards, last to pitch 300 innings (in a season) … he was the single player I wanted to talk to the most."