Andre Ward on the value of telling his story and the state of boxing today

When Andre Ward walked away from boxing at the age of 33, his record spoke for itself: 32-0. But for Ward, that wasn't the whole story.

"I didn't feel like the media deserved to have my full story on blast," Ward said. So he kept quiet about some of his most formative experiences: growing up in Oakland with parents who suffered from substance use disorder. His mom was absent; his dad relapsed when Andre was a preteen and died when he was 18, spinning his life into turmoil.

"I like to call it my season of rebellion, when I was just like, 'I don't want anything to do with authority, God, nothing. I'm gonna live my life and do it my way,'" he said.

Ward showed early promise as a boxer, winning the U.S. under-19 national championship weeks before his father died. But when he began using substances and selling drugs after his father's death, his future in the sport was in jeopardy.

"I knew how I wanted to use drugs, I wanted to smoke weed, I wanted to drink, and I had an appetite and a desire for those things daily," he said. It wasn't until Ward reconnected with the religion of his youth - Christianity - that his life and career turned around.

"Once I began to look up and humble myself and acknowledge my faults and my wrongs, and stop blaming mom, stop blaming dad, and ask for forgiveness - the peace that I felt, the power that I felt connected to my life, it can never be denied," he said.

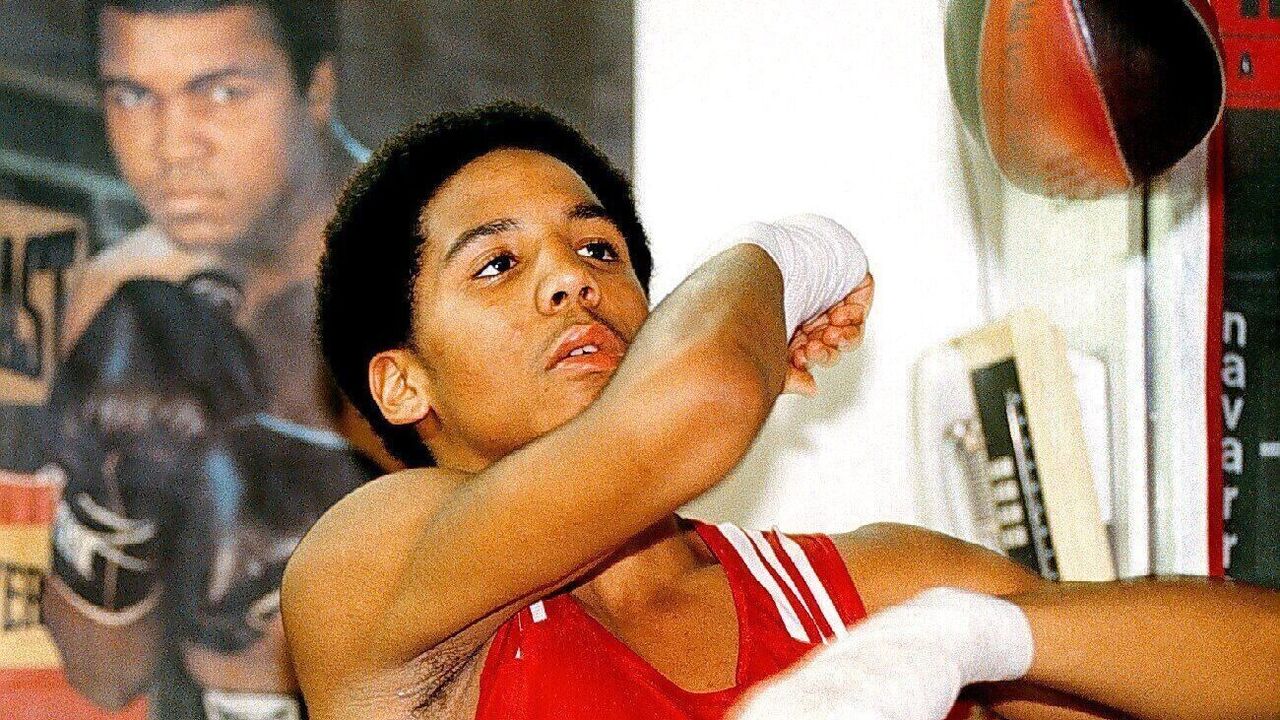

Ward put his head down and got to work, earning a reputation for fighting the best in his category and becoming an Olympic gold medalist at Athens 2004.

"When the world saw me in 2004, I was just fresh off the streets and was just trying to figure it out," he said. "I've tried to maintain my consistency with how I live my life. I'm not perfect, but I've tried to maintain that consistency, and then speak when it's appropriate."

Consistent might be the best way to describe Ward's career - his last recorded loss was as a 13-year-old. As a professional, he won eight world titles in two divisions. He also recorded 16 KOs throughout his career, the most famous of which was arguably his last: an eighth-round TKO of Sergey Kovalev to defend the WBA, WBO, and IBF light heavyweight titles.

When Ward retired in 2017, his body of work felt complete, aside from one lingering thing: opening up.

"I knew I was going to tell my story at one point in time," he said. But he had stipulations. It needed to be "in my own words, where I can control how this thing is being told."

Years went by and healing worked its way through Ward's family. He re-established ties with his mom and found a second career as a youth minister. He began to consider that there'd be value in speaking openly about what he'd experienced. Last year, he released a documentary and an autobiography titled "Killing the Image," a process that gave him complete control over how his story was told.

theScore recently caught up with Ward to explore how that process has impacted him, and what he thinks of the state of boxing now.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

theScore: For most of your career, the story was always that we didn't know the full story about you. You kept your cards close to your chest. In the last year, that's changed. Now, you've released the documentary and the book. I'm wondering what life's like for you now that you've told your story on your terms?

Ward: I don't think much has changed for me externally. Internally, I feel a relief. I feel like a weight has been lifted. My unwillingness to share everything was strategic. I saw the landscape and I saw how fighters use their personal stories to sell fights and to get headlines. There's nothing wrong with it. I just looked at it differently. Like, I'm an '80s baby. I was always taught we don't share our personal business like that. I'm aware of the world that I live in. Now, when people share, overshare, they share too much. I just have always been like, 'Nah, my mom and dad's struggles - that's personal. Our family struggles - that's not for the world.' But it got to a point where I started to feel selfish to not share. So now the key was, 'Okay, I'm going to share, I want to share, but when's the right time?'

What has surprised you most about the way the doc and the book have been received?

I was expecting some negativity. I don't know why I felt like that. I guess I'm just kind of used to living in this world and being on social media, you always expect the one person or the few people. I haven't gotten any negativity. It's only been encouraging stuff. I've even had some people that have been like, 'Man, I feel so bad, you went through so much.' It's almost like an empathy. They're like, 'I didn't know you were struggling like that, as a young kid and as a teenager.' So that's been a little surprising.

I think that a lot of people didn't really know about how your growing-up years affected the decisions that you made in your career. Can you talk a little bit about that?

I think that a lot of this stuff was good and bad, right? I think the good part was it just gave me a drive. I don't know how to quantify how the struggle gave me drive, but I think that it had something to do with it. I just always wanted to be good. I just didn't want to settle. And I think internalizing mom not being there, some of dad's struggles and stuff like that, it just made me sort of tough. It made me sort of willing to go that extra mile in certain areas.

But there's also sort of a downside to not having a mother there and being raised by a bachelor. That sensitive side I didn't have, it took me years to realize how that affected me. So in my relationship with my wife, I'm guarded in certain areas, I'm unwilling to trust in certain areas, or I'm not really comfortable talking about certain things. It took a lot of work to realize my mom not being there affected me in my early 20s, 30s, and in manhood. But I'm grateful for that process as well because that's what the book gave me. That's what the doc gave me, I was able to talk about my processes and my counseling and my acknowledgments of things and the path that I had to walk and still have to walk to hopefully inspire, but also give a roadmap to other people.

You're now enjoying a second career in Christian ministry. How did you hear God speak to you about going into ministry?

I think it was a desire, right? Even before I understood what that meant, I was like, 'Man, I could kind of see myself doing this.' Then, my godfather, he would mention that, 'Man, you're gonna be a preacher one day.' (At the time) I don't know what that means, but alright. Then I met my pastor, and then he started saying it. So I'm like, 'OK, there's something here,' the desire started to get stronger.

Then, I got an opportunity to speak and I'm like, 'Oh, man, wow, that was scary. But I think I can actually do this.' I'm at a point now, at 40, where I realized clearly that speaking, being able to communicate my thoughts, being able to have good thoughts and communicate them in a way that people can understand, it's one of my gifts. So I just think that over time, as I've gotten older, I've accepted that speaking is one of my things. And not just speaking but sharing the gospel. That's what my call is.

When you look at boxing today, and the ways that it's changed since you retired, what stands out to you the most?

I think the mentality of fighters is different. I love some of that. And then some of it I don't love. The part I love is that (today's) fighters want more money for the least amount of risk. And I subscribe to a lot of that, because for so long, in boxing historically, fighters took huge risks. Risks they probably shouldn't have taken for little to no money at all. So that landscape has changed.

My only problem with that is you have a generation of young fighters who don't want to fight the other best guy or the other two best guys in the division, but they want to be considered the best in the world or the GOAT. It's like, hold on a second. One thing that will never change is you cannot say that you're the best until you fight the other best. Then we'll see who's the last man or last woman standing. That's the only way we can figure that out. Have the new mindset, be about your business, get your money. But you can't claim to be the best without facing the best.

I think that there should be a balance between getting your money and proving that you're the best. That's why we're in it. That's what this sport was built on. So we can't get around that.

What about these exhibition fights? You said in November that you would be open to coming out of retirement to fight Jake Paul. Still stand by that?

In the right situation, yeah. If it made sense. I would do something like that. I don't have a problem with it. Some people are threatened by it, 'Oh, it's ruining the sport.' I'm like, 'Nah, there's a lot of other things that are actually ruining the sport that we don't want to address.'

I actually love it because you have crossover appeal with a guy like Jake Paul, where his whole fan base is watching and bringing eyeballs and attention to our sport. He's selling out arenas. You've got to respect that. So, I actually like that they're doing stuff in Saudi Arabia now, Tyson Fury just had an exhibition, and Anthony Joshua has got one coming up with an MMA fighter. I love it. I'm like, 'Let's talk about our sport. Let's have it in the mainstream spotlight.' So, I don't have a problem with it. Given the right situation, I might jump in there, too.

Is this hypothetical or do you think there's a chance the right situation will come about?

I'm the type of person where it's hard. Like, nobody has really called my name since I retired and I really take that in a respectful way. You know, I just think that it's a big risk for a lot of people. (Chad) Ochocinco, a former football player and now analyst, you know, he pokes at me online and he says he wants to do something like that. So, maybe (I'd do) something like that. But it's got to be the right situation to sort of get me off the couch and get me back in a boxing gym. It's got to make a whole lot of sense. So far, it hasn't.

Jolene Latimer is a features writer at theScore.