To pee or not to pee? That is the question that divides tennis

During this year's men's Wimbledon final, after dropping an ugly second set to Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic walked off Centre Court and into the tunnel. He returned about five minutes later to find a restless Federer already waiting at his own baseline, ready to serve.

Djokovic had left the court under the pretense of needing to use the bathroom. But his former coach, Boris Becker, knew from experience that there was likely more to it than that.

"That's what he does sometimes," Becker told the BBC during the broadcast. "He is changing his shirt. He wants a moment for himself, some peace and quiet. He will want to gather his thoughts to reset for the third set."

And so Djokovic did just that, before winning the next set en route to a dramatic victory in five. Could he have pulled it off without the stoppage? Who knows.

Between-sets bathroom breaks have become something of a fault line in pro tennis. While they fall within the rules, it's an open secret that they aren't always (or even often) used for their expressed purpose, but rather as a means of psychologically regrouping or disrupting an opponent's momentum.

The question is: When it's being used for the latter, is that a bad-faith circumvention of the rules, or just basic gamesmanship? It depends on whom you ask.

"If it's within the rules, you can do whatever you like," Ash Barty said at a recent event.

Strictly speaking, yes. But are the rules being abused in this case?

"Of course," Sloane Stephens replied, drawing out the second word. "My feeling is, if you're not ready to play, and you can't compete, don't get out there.

"Like when I played Cincinnati in (2017). For like seven matches in a row, I had someone go to the bathroom or call a medical timeout. And I was like, All of these people are not sick or have to pee all the time. That's not how that works."

This year, the WTA seemed to acknowledge that bathroom breaks are an issue, reducing the number of permissible trips to the loo from two per match to one. Most of the female players I spoke to insisted they'd never taken advantage of the bathroom-break allowance, though most believed their opponents had.

"If you check, I didn't go out many times, and when I went out I needed it," Simona Halep said. "But it's good that we have only one now. Some players are doing this, they take advantage. You have to be strong enough to get back in the rhythm."

"I don't remember one time in a match where I had to pee," Stephens said. "You're running around, sweating. That just doesn't come to mind. Maybe if you have a weak bladder? I dunno, it may happen. But I think it was being abused a bit, so I'm glad they did change the rule. I haven't heard anything since the rule change. I don't think anyone's gone over (one break) because no one wants to pay a fine. Of course not. So they're like, I'm just gonna hold it."

Singles tennis is defined in large part by the isolation of the players. There is nowhere to hide on a court, and no one to defer to. You might gripe with the chair umpire, seethe at your box, bellow to the crowd, or ask a ball boy for a towel, but for two, three, four, sometimes five hours, you can't really have a conversation with anyone but yourself. (Women are permitted coaching timeouts at regular tour events, but not at Slams.) So, it shouldn't be surprising that players look for escape hatches where they can find them.

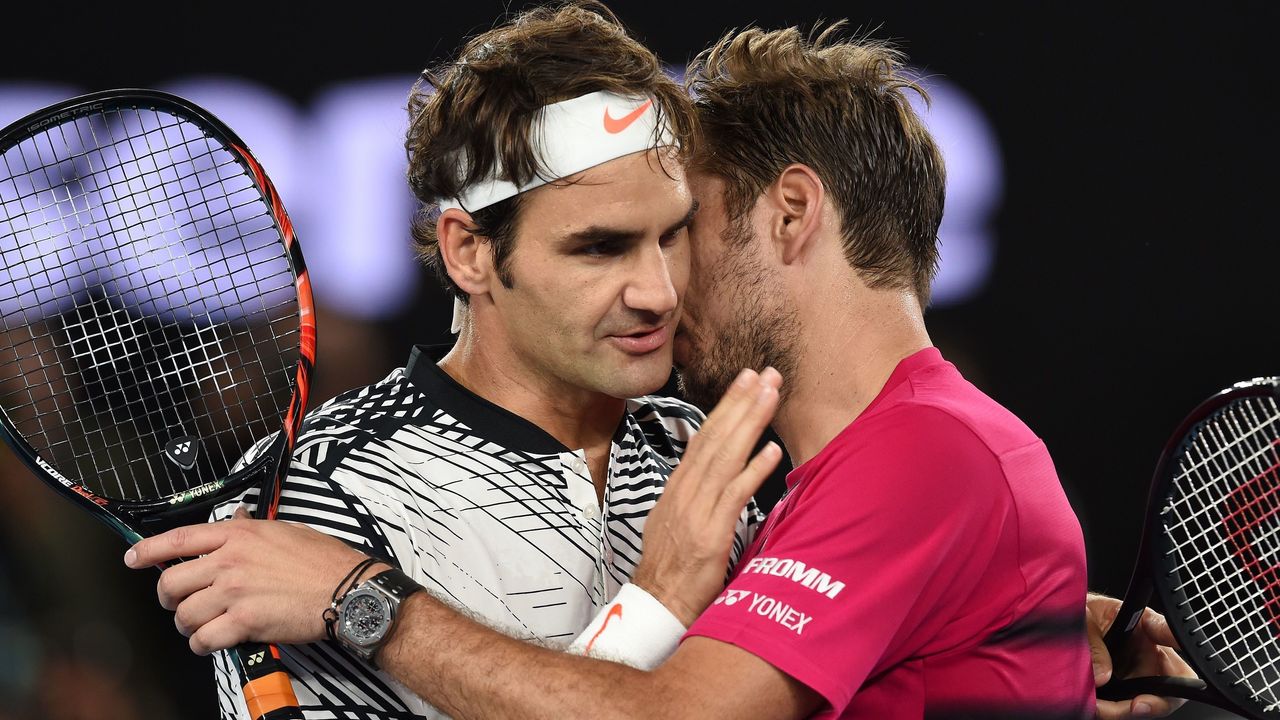

After watching a two-set lead evaporate in the 2017 Australian Open semifinals against Stan Wawrinka, Federer requested an off-court medical timeout before the fifth, which he later admitted helped his mind more than it did his body.

"I only really did take the timeout because I thought, 'He took one already, maybe I can take one for a change,'" Federer told reporters after winning the match. "I think these timeouts, I think they're more mental than anything else. … For the first time, maybe, during a match, you can actually talk to someone, even if it’s just a physio."

Bathroom breaks - though they don't offer companionship - can provide something similar: a chance to step away from the raucous environs of a stadium court, have a moment of quiet, and collect your thoughts. You can even have a conversation with someone - even if that someone is you.

"I stood in front of the mirror with sweat dripping down my face, and I knew I had to change what was going on inside," Andy Murray explained of the bathroom break he took before the fifth set of his 2012 US Open final against Djokovic. "So, I started talking. Out loud. 'You are not losing this match,' I said to myself. 'You are not losing this match.' I started out a little tentative, but my voice got louder. 'You are not going to let this one slip. This is your time.'

"At first, I felt a bit weird, but I felt something change inside me. I was surprised by my response. I knew I could win."

And he did.

About two years after losing that match to Murray, Djokovic did the same thing after dropping the fourth set from 5-2 up against Federer in the 2014 Wimbledon final.

"It's like Andy in the US Open," Djokovic said. "Except that I wasn’t looking in the mirror, I was looking at the toilet seat. ... I needed some time to refocus and forget about what happened in the fourth set, forget about the missed opportunities and move on."

Djokovic, too, went on to win in five sets.

There's no realistic enforcement mechanism to ensure these breaks are being used in the manner for which they're intended. When they leave the court, players are supposed to be accompanied down the tunnel by a line judge, but they obviously aren't being chaperoned into the bathroom, nor would you want them to be. But perhaps there can be stricter enforcement of time limits on those breaks, which are supposed to last two minutes but almost always drag on far longer.

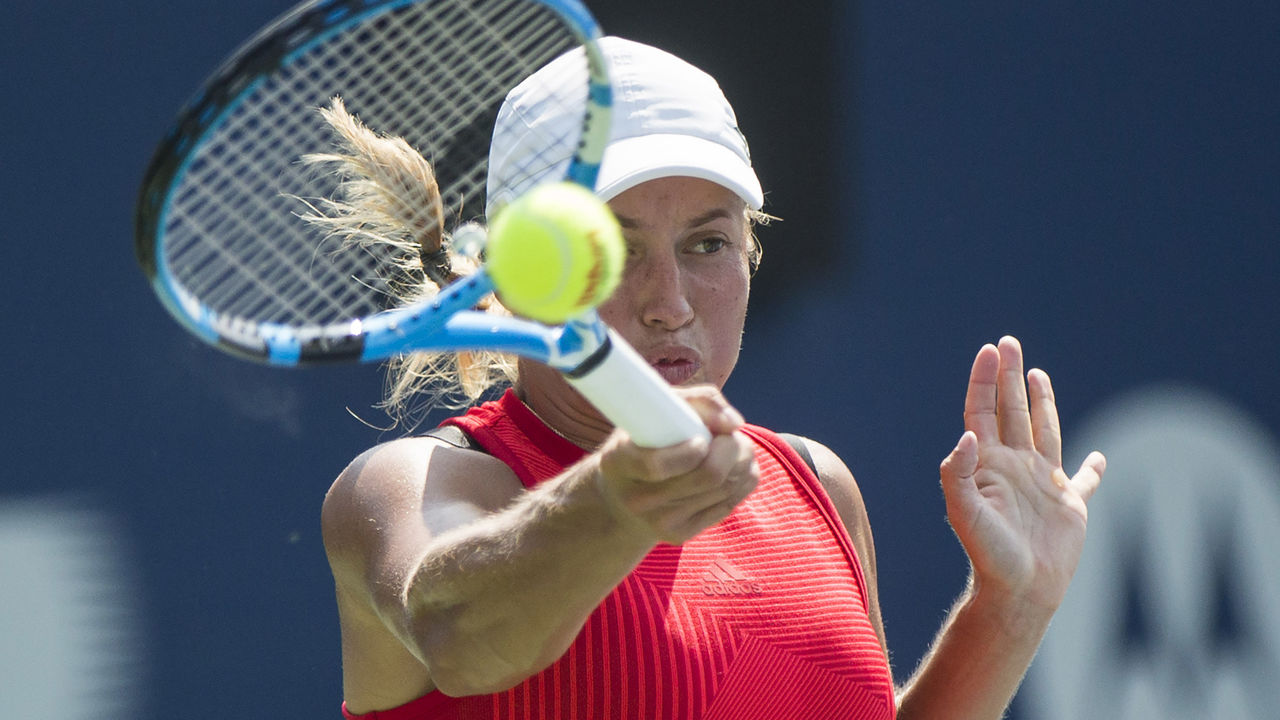

In Cincinnati this year, Yulia Putintseva took an off-court break after the first set against Stephens that lasted 10 minutes. "She will work your last damn nerve," Stephens said of Putintseva in her post-match press conference, adding: "If it's not one scam, it's another." If the bathroom break is meant to be about your comfort, it can sometimes be used to provoke an opponent's discomfort.

Anecdotally, the consensus among the women interviewed was that it's exceedingly rare for an actual bathroom emergency to interrupt a match.

"I can't remember ever using a toilet break," Barty said. "I know I've gone off court to change, once in Sydney, maybe last year or two years ago. But I don't know that I've ever taken a toilet break."

This was a recurring theme among the women, who pointed to the necessity of changing clothes as the biggest reason for leaving the court.

"I don't remember if this was the French or Australian, but I wanted to change my shirt," Naomi Osaka said. "So I asked if I could go to the bathroom, but then (the chair umpire) was like, 'You only get one bathroom break.' So I was like, 'OK, can I go change my shirt, though?' And she was like, 'It's gonna count as a bathroom break.' And I was like, 'Oh, that's interesting.' So, yeah, I didn't end up changing my shirt."

This is probably a discussion worth having on its own. After a code violation was issued to Alize Cornet at last year's US Open for briefly removing her shirt on court because it was on backward, the WTA issued a statement insisting there was "no rule against a change of attire on court," while the USTA said women "will not be assessed a bathroom break" when they leave the court to change. Evidently, not all the Slams have adopted the same policies.

Sometimes, though, even if a break is employed with the intention of changing one's wardrobe, it can ultimately present other benefits.

"I never go to the bathroom during the match, because I don't want to waste time, and I feel like I just want to play, you know?" Karolina Pliskova said. "But actually this year I did in Wimbledon (in the third round against Hsieh Su-Wei), not because I wanted to change the momentum, but I just felt like I was too sweaty, I wanted to change my socks. And then I just said ... because it was Court 1, it was one set all, I lost the second set, and I just said, I need to walk a little because everything just went too fast.

"But normally, I don't do these things. I know some players, they just use this as a way to change the match or something. But I just prefer to continue and change it in a normal way, not this way."

As to whether the use (or abuse) of bathroom breaks is a problem that needs solving, there's no right answer. You can argue that off-court timeouts sap some of the drama that comes with the naked isolationism inherent in tennis. You can also argue that players shouldn't be subjected to such intense and unwavering scrutiny, and should be allowed a moment or two to step away and clear their heads. What if there was more transparency so breaks wouldn't need to be taken under the guise of a bathroom emergency? What if players were simply permitted to leave the court once per match without having to offer an explanation?

In any case, it seems clear that players see benefits in doing so. Tennis, more than perhaps any other sport, is played in the mind as much as it is in the body. And just like the body, the mind occasionally needs respite.

"Maybe it's bad," Pliskova said of her typical unwillingness to leave the court between sets. "Maybe if I do it a little bit more often, I'll win more matches."

Joe Wolfond writes about basketball and tennis for theScore.