Film Room: How the Packers are winning despite Aaron Rodgers' injury

As he leaned over from shotgun, Aaron Rodgers’ left knee buckled backward and then forward.

He hobbled through a five-step drop and scanned the Dallas Cowboys’ split-field safeties. Both safeties rotated: the left to the middle, the right underneath. With the coverage clearly zone, Rodgers hit the top of his drop and looked left to receiver Randall Cobb running a corner route. Rodgers hitched once.

His left leg planted. His torn left calf, shredded like the sod at Lambeau Field, stretched. Suddenly the ball spiraled from his hand. It had enough trajectory to fly through the 24-degree air, enough lift to sky over the nickel cornerback’s head and wobble nose-down into the hands of Cobb, who tiptoed for the 31-yard catch.

Many of Rodgers’ dropbacks in the Green Bay Packers’ divisional-round win went like that. His calf had frozen up and robbed him of his mobility. He spasmodically extended plays, only a couple as dangerous as they were pre-injury. And when he tried to stick in the pocket, which head coach Mike McCarthy molded specifically to limit Rodgers’ movement through pistol and shotgun sets, he slid around noticeably slower, which affected his footwork.

Rodgers wasn’t able to rotate his hips at all times and threw off of his back foot. He leaned on his right leg for power and pressed hard off of it as he dragged his left leg through the pocket. It was particularly noticeable at the top of his dropbacks. Yet, there were still moments of vintage Rodgers.

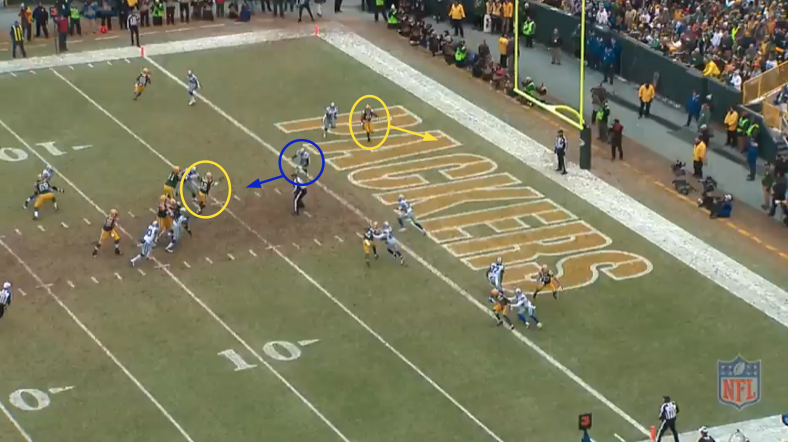

Midway through the first quarter, on third-and-goal, Rodgers took one long step and set his feet and raised the ball to his right. A trio of Packers weapons were jammed and jumbled by the Cowboys’ defensive backs. They had been the main reads on the play, one designed to get the ball out of the quarterback's’ hands quickly.

Rodgers hustled in-between the left guard and center and used his legs to make the play. In the past it had been no problem. Now?

From the goal line, a Cowboys safety barreled toward Rodgers, whose eyes flashed up as he flicked the ball to tight end Andrew Quarless on a slant route behind the same safety. Touchdown.

If Rodgers’ legs weren’t going to do the job, then his eyes would have to. He’d worked on them over the years, perfecting keeping them up while running and moving defenders as he slid in the pocket. He learned to hold linebackers and safeties in the seam to give his receivers time to run away from coverage. He learned to make defenders move a muscle, shift their weight an ounce, just enough to put them out of arm's reach of the ball. He learned to find and widen holes in zone coverage. Now all his training was coming together against the Cowboys, because of injury, no less.

He had no other choice. Through nearly three quarters, he was limited more than ever. He misfired on routine throws, his accuracy ranging from too low to too high, because he couldn’t establish a strong base. It was not until less than three minutes were left in the third quarter did his calf warm up and flashes of his old self popped up.

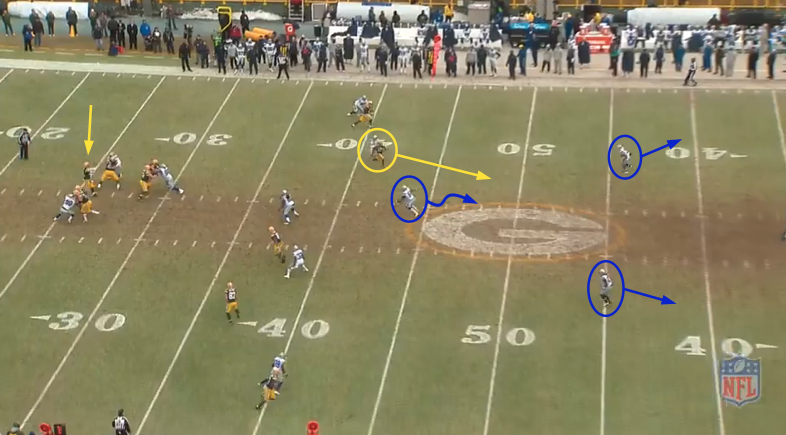

On first-and-10 late in the third quarter, Rodgers quickly set his feet from shotgun and again read the safeties. For much of the game, they had showed a two-deep shell and then rotated down to a single-high shell. Now they showed two deep again, with the free safety staggered four or five yards ahead of the strong safety, and both backpedaled to Cover 2.

With the Packers’ two receivers outside running vertical routes, the safeties stayed deep and the key became the middle linebacker. He side-saddled down the seam, his shoulders mirrored Rodgers’ eyes.

Without moving his feet, Rodgers stared at his tight end running a stick route. The middle linebacker waited and waited for the throw when, abruptly, Rodgers looked back to his left and flung the ball to Cobb on an in-breaking route in-between the middle linebacker and nickel cornerback for 26 yards.

Rodgers warmed up at the right time, and the Packers started to look like they deserved to advance to the NFC Championship Game against the Seattle Seahawks, despite trailing 21-13.

Rodgers completed 10 straight passes from the end of third quarter to the end of the fourth. He caught fire in the cold, blazed past the Cowboys’ secondary to the tune of 316 yards. His performance had looked sloppy by his standards, but it was good enough. He had thrown nine yards per attempt and completed 68 percent of his passes. He also tossed three touchdowns, including the gutsy game-winner.

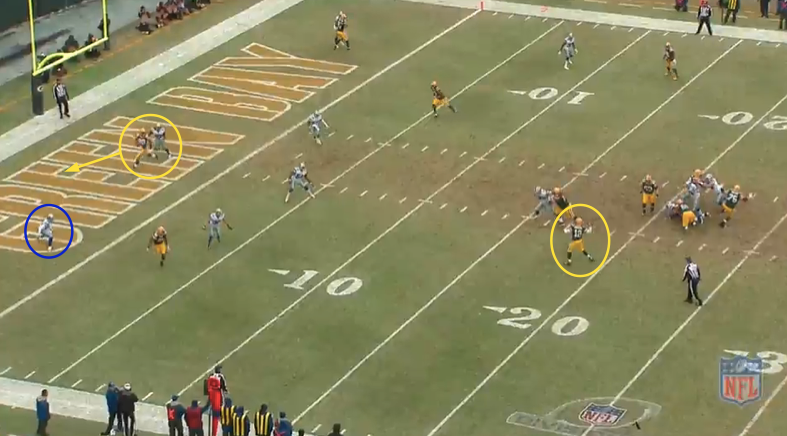

With less than 10 minutes left in the fourth quarter, down 21-20, Rodgers dropped back three steps, looked left to a tight end then looked right to a receiver. The tight end, Quarless, seemed open when the cornerback pulled back, except the free safety jumped in front of him. The receiver, Cobb, was open in the flat and could shake free from some of the four underneath zone defenders, but Rodgers looked elsewhere.

The pocket pushed back, the air in it slowly leaked out like a flat tire, and Rodgers labored left. He flushed out of the pocket and kept his eyes up. The Cowboys’ underneath defenders froze and the deep-third cornerback that had covered Quarless muddled his feet. Rodgers hopped left, jump-started his torn calf and darted the ball to back-side rookie tight end Richard Rodgers in-between two defensive backs for the score - 26-21.